|

Somewhere, over the Red Sea: The story of the Exodus (Part Two) Posted: 21st August, 2011 Last updated: 7th May, 2012 |

|

|

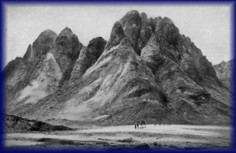

WE HAVE SEEN THAT YAM SUF OF THE EXODUS can definitely be identified with the Gulf of Aqaba. However, Exodus 10:19 offers a window of hope for traditionalists who, for many decades now, have rejected the Gulf of Aqaba as the "water of crossing". They believe the Red Sea Moses spoke of was right on Egypt's eastern border. A look at a map of the Egyptian delta area, where the Israelites lived, reveals a few possibilities. Let Rabbi Nosson Scherman explain: This may have been the Gulf of Suez, which branches northward from the Red Sea [by modern geographical convention] and separates Egypt from the Sinai Desert. It may be that the Sea of Reeds was the Great Bitter Lake, which is between the Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea; or the large delta at the mouth of the Nile, in the north of Egypt or it may have been the southern Mediterranean (1993, p. 367). Here four options are presented. Hardly anybody supports the Nile delta option and, frankly, we consider it is not worth considering on the grounds that it falls short of the biblical description on numerous counts. The Mediterranean Sea option, too, although supported by some noteworthies, falls down on one simple biblical criterion: Then it came to pass, when Pharaoh had let the people go, that God did not lead them by way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near; for God said, "Lest perhaps the people change their minds when they see war, and return to Egypt" (Ex. 13:17). A Mediterranean Sea "crossing" (if it could be called such) would require that the Israelites did exactly what these words tell us they did not do - take the coastal route. What about the idea that the Red Sea was nothing but a shallow lake, such as Lake Timsah, Lake Balah, or the southern extension of Lake Menzaleh located between the northern tip of the Gulf of Suez and the Mediterranean Sea, somewhere near today's Suez Canal. Rarely in the annals of learning has such a dumb idea been parroted by so many for so long for so little reason. The evidence trotted out to support the idea is, frankly, laughable. Above all, critics resort to a charming piece of reasoning. The Hebrew term for Red Sea is, as we have noted, "Yam Suf ". "Yam" is the standard word for sea and presents no interpretive problems. "Suf ", we are told, means "reeds". Since these grow in shallow water, Yam Suf must be a shallow lake or marsh covered with reeds. Thankfully, a handful of modern scholars is beginning to recognize the folly of this old saw. Bernard Batto puts it this way: If there is anything that sophisticated students of the Bible know, it is that yam sûp, although traditionally translated Red Sea, really means Reed Sea, and that it was in fact the Reed Sea that the Israelites crossed on their way out of Egypt. He goes on to say that, We don't know who first suggested the translation Reed Sea. The 11th-century medieval French Jewish commentator known as Rashi accepted a connection between yam sûp and a marsh overgrown with reeds. The "Reed Sea" hypothesis has now become so widely accepted that one can scarcely pick up a handbook or treatise on the Bible, regardless of the author's theological affiliation or scholarly bent, that does not espouse the theory that yam sûp means Reed Sea when used in connection with the body of water the Israelites passed through on their way out of Egypt. Batto, an expert linguist, demolishes the popularly-presented idea that "yam suf " is to be identified with an area known as p'-t_wf in Egyptian texts such as Papyrus Anastasis III where it is used to refer to "a papyrus marsh or district, not to a lake or body of water" and concludes that, "Historically, it came to mean the Red Sea and what lay beyond". In other words, Yam Suf referred to all the parts of what we today know as the Red Sea! It did not refer to some marshy bog or lake. For starters, the whole reedy lake idea is obviously at loggerheads with the scriptural record which, no matter how you slice and dice it, cannot be interpreted as allowing for a crossing through a shallow swamp, lake, or lagoon. That Pharaoh's massive army could be swallowed up to the last man in maybe 35 feet of water, as would be the maximum depth in the favored candidate for the privilege, the Great Bitter Lake, is ludicrous. Furthermore, Exodus 15:5 says of the Egyptian victims of the collapsing waters that, "They sank to the bottom like a stone". To have sunk, the air must have been forced out of their lungs, making their bodies denser than water. Inundation by a few meters of water would not have that effect. The bodies would slowly rise to the surface. Worse, the idea has a fatal flaw. The lakes proposed may not have existed in Moses' day; they came into being with the digging of the Suez Canal: On its way through Lake Timsah (at Al Ismailia), the Canal cuts into the Great and the Small Bitter Lakes. These lakes were dry salt valleys, 13km long and 5km wide, until they became part of the Suez Canal.16 Anybody heading that way would not have come across any "sea" to cross. Encyclopedia Britannica says, On March 19, 1869, the waters of the Mediterranean were admitted to the Bitter Lakes, which within a few weeks became filled and thereby converted into a navigable channel. (Suez Canal). Some scholars believe that in Moses' time these lakes did have water in them, and quote Egyptian inscriptions of the Twelfth Dynasty that apparently speak of the Great Bitter Lake as an undrinkable "lake".17 Even assuming this inscriptional evidence is correctly interpreted, it gives little comfort to the proponents of a Great Bitter Lake crossing. A shallow lake would never have been dubbed a "sea". The theory's problems mount further when you examine the fundamental premise, that "suf" must mean reeds. The term is used to describe waterside plants in Exodus 2:3-5 alone. Jonah speaks of having "weeds" (suf) wrapped around his head in the Mediterranean Sea. "Yam Suf " could just as likely mean "Sea of [sea]Weeds" as "Sea of Reeds", in which case it could be a very appropriate designation for a large, salty body of water. Other possibilities are equally persuasive. As Batto points out, the Semitic root "suf/sof" can mean "end", as in 2 Chronicles 20:16 or, in verbal form "come to an end". Both the Gulf of Suez and the Gulf of Aqaba are "dead-end" seas, and it may be that property implied in the name Yam Suf. Its verbal form appears in a number of passages such as Zephaniah 1:2 and Esther 9:28. Equally possible, therefore, is that the name means something like "Consuming Sea". Now why might it ever have been given that name? Think about it. Obviously, if the Gulf of Aqaba qualifies as the sea of deliverance for Israel, Mount Sinai cannot be located in what is called today the Sinai Peninsula. It must be found somewhere in the north-west corner of modern day Saudi Arabia. Click here to view a Google Earth image with some of the chief proposed crossing points marked out. Please note that this image does not include any proposed routes for Israel's journeys after crossing the Yam Suf. Suez or Aqaba?We have shown that, although Yam Suf generally refers to the Gulf of Aqaba in biblical accounts, the possibility remains that it refers to the Gulf of Suez. May the Israelites have crossed it rather than the Gulf of Aqaba? What evidence or reasoning can be brought to bear on settling this knotty question? The truth is, no evidence in the forensic sense can be found. One colorful adventurer who has been a living bone of contention among Bible students claims to have found hard evidence in the Gulf of Aqaba in the form of chariot wheels. Ron Wyatt's official website makes the following claim: Ron Wyatt, when searching for the Red Sea Crossing Site, found a beach on the Gulf of Aqaba which could easily have held the multitude, their flocks, and also pharaoh's army. Ron went diving in the Red Sea and found various artifacts which he identified as chariot wheels and chariot cabs. He presented his findings to the head of antiquities in Cairo Egypt, who identified the chariot parts as those from the 18th dynasty.18 This author believes Ron Wyatt was dead right on one point - the location of the Red Sea crossing. However, Wyatt appears to have been inclined to exaggeration and spin in some of his publications and presentations. Before his death in 1999 he claimed to have found Noah's ark, the Ark of the Covenant (with some of Jesus' blood on it), Sodom and Gomorrah, the tower of Babel, the true site of Mt. Sinai, the original stone tablets of the Ten Commandments, and the site of Jesus' crucifixion. Did he, in truth, find chariot wheels from the time of the Exodus? Nobody knows the whereabouts of the recovered wheel today. The antiquities expert is identified somewhere as Nassif Mohamed Hassan, but a Google Scholar search on the name yields not a single result.19 If we have no archaeological evidence proving where the Israelites crossed, we must resort to intelligent elimination of possible alternatives. Does a Gulf of Suez crossing make sense? Might not the Israelites have surged south from Rameses and travelled along the western side of the Gulf of Suez before crossing it at some point? What does this scenario have going for it, and what against it? ForTwo factors appear to lend it some support. First, the description in Numbers 33 certainly can be read to suggest a crossing very soon after leaving Egypt, a scenario that would favor a Suez crossing over an Aqaba one: Then the children of Israel moved from Rameses and camped at Succoth. They departed from Succoth and camped at Etham, which is on the edge of the wilderness. They moved from Etham and turned back to Pi Hahiroth, which is east of Baal Zephon; and they camped near Migdol. They departed from before Hahiroth and passed through the midst of the sea into the wilderness. (vss. 5-8). A mere three stopovers are mentioned between Rameses and the crossing. Taking Rameses to be located near modern Qantir, the walk to one logical crossing point on the Gulf of Suez (between Adabiya and Uyun Musa) would have been about 75 miles. Taking each stopover to represent a day's journey would require walking 25 miles per day, a difficult but do-able proposition under the circumstances. If they walked further south and crossed between Ain Sukhna and Ras Sudar, an extra fifteen miles would have been required, again possible if they took an extra day or two. The Gulf of Aqaba, by contrast, is over 200 miles from Rameses, out of the question for a three or four day walk. Jewish tradition stretches the time taken to seven days, mainly in order to peg the crossing to the last day of unleavened bread (21st Nisan). It adds in an extra day on account of the apparent order to retrace their steps (Ex. 14:2) and then a few days rest at Pi-Hahiroth before crossing (Scherman 1993, p. 369). Second, the text provides an interesting bit of data: Speak to the children of Israel, that they turn and camp before Pi Hahiroth, between Migdol and the sea, opposite Baal Zephon; you shall camp before it by the sea. For Pharaoh will say of the children of Israel, "They are bewildered by the land; the wilderness has closed them in" (Ex. 14:2-3). A Google Earth study of the terrain on the west side of the Gulf of Suez shows an east-west ridge of mountains rising abruptly from the low plain at Ain Sukhna and rising close to 2000 feet, thus presenting an impassable barrier to anybody fleeing pursuers. Maybe the crossing took place here. AgainstThe apparent fit, though, melts away when more information is examined. Consider a vital fact, one that shatters all traditional theories about crossing points: Then it came to pass, when Pharaoh had let the people go, that. God led the people around by way of the wilderness of the Red Sea. And the children of Israel went up in orderly ranks out of the land of Egypt (Ex. 13:17-18). Israel crossed the Yam Suf after going "out of the land of Egypt". Now where was the eastern border of ancient Egypt? Hoffmeier tells us that it was around the "reedy, marshy lake district. south of Tjaru/Sile"; in a word, the eastern border could roughly be defined as a line running from the tip of the Gulf of Suez north to the Mediterranean Sea. Any crossing of the Gulf of Suez (or of any of the reedy marshes presumed to have existed at the time) would be taking place in Egypt, barely a stone's throw from the Land of Goshen, a scenario completely incompatible with the biblical facts just presented. In addition to the above verse, the testimony of Exodus 14:10-12 also proves irrefutably that by the time the Israelites had reached the crossing point they had left Egypt far behind. Basic psychology points in the same direction. To cross the Gulf of Suez the fleeing Israelites would have needed to head south from Rameses. What hope would Moses have had of convincing them to flee south when they were raring to head east? In the months leading up to the departure, Moses had thoroughly prepped the people for their deliverance: Moreover God said to Moses, "Thus you shall say to the children of Israel: 'The Lord God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you. This is My name forever, and this is My memorial to all generations.' Go and gather the elders of Israel together, and say to them, 'The Lord God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, of Isaac, and of Jacob, appeared to me, saying, "I have surely visited you and seen what is done to you in Egypt; and I have said I will bring you up out of the affliction of Egypt to the land of the Canaanites and the Hittites and the Amorites and the Perizzites and the Hivites and the Jebusites, to a land flowing with milk and honey" ' " (Ex. 3:15-17). The people believed Moses' words (Ex. 4:29-31) and so, when the time came, they were raring to go - east, that is. That they took a basically direct route to the Promised Land is indicated by Exodus 13:17-18: Then it came to pass, when Pharaoh had let the people go, that God did not lead them by way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near; for God said, "Lest perhaps the people change their minds when they see war, and return to Egypt." So God led the people around by way of the wilderness of the Red Sea. The import of the verb "to lead around" is unclear, and no case can be built upon it. Its general sense seems to imply something like "encircle, go around", but is translated as "carry away" in the NKJV20 version at 1 Samuel 5:9. They went along/around "the road to the Red Sea wilderness" or, if it is meant as a proper noun, the "Red Sea Wilderness Road". Without any further clarification, it could have been a road heading south to the Gulf of Suez or a road heading east to the Gulf of Aqaba. Further clarification, however, is supplied by this verse. The "Land of the Philistines Road", known later as the Via Maris, hugged the Mediterranean coast all the way to the land of Canaan. Who can miss the implication that the Red Sea wilderness road led to Canaan, too, rather than deeper into Egypt? Stop and think. Had Moses instructed the Israelites to head directly south, parallel to the eastern border and deeper into Egyptian territory, total confusion and distress would have gripped the people. (Their journey did involve a considerable south-heading leg after leaving Egypt, but the biblical account tells us they departed from Egypt very quickly, meaning they headed east at the outset - the direction for the fastest trip to the border.) Under such conditions of mental distress Moses would have had zero hope of organizing them into orderly ranks. They left with a "high hand" (Ex. 14:8) of triumph, not in apprehension and anxiety. They were heading for the land promised to them. Commonsense suggests that the "Red Sea Wilderness Road" was a name for the Egypt-to-Aqaba section of a well-known ancient highway, the King's Highway, of which Wikipedia says, The King's Highway was a trade route of vital importance to the ancient Middle East. It began in Egypt, and stretched across the Sinai Peninsula to Aqaba. From there it turned northward across Jordan, leading to Damascus and the Euphrates River.

This road, which skirted east of the Promised Land, is mentioned a couple of times in the Pentateuch in the context of the Exodus (Num. 20:17, 21:22). Most texts attach the name "King's Highway" to the section heading north from Aqaba (near Eilat), which fits the usage in the biblical passages. Some writers suggest that this Egypt-to-Aqaba leg of the highway follows a modern road, known as the Taba-Naghl Road, running generally southeast from Egypt across the Sinai Peninsula. That idea makes a lot of sense. After the crossing, the Israelites rejoiced like few had ever rejoiced before. Read the song of triumph in Exodus 15. They were evidently confident that now all their problems of an Egyptian nature were far behind them. Had the crossing occurred in the upper reaches of the Gulf of Suez (or across a marshy bog) they would have had little cause for confidence. How could they have known that the entire Egyptian army had been obliterated? For all they knew, a second force was at that very moment making its way around the tip of the Gulf of Suez and bearing down rapidly on them. A Gulf of Aqaba crossing, however, meant complete safety. The prospect of a second Egyptian army bulldozing its way around the top of the Gulf of Aqaba and down through Midianite territory (remembering that the Midianites were friendly to the Israelites) to snafu the fleeing throng would have been unthinkable. The timingWe need to consider the first point raised above in support of a Gulf of Suez crossing - the timing - more carefully. Bryant Wood brings this point out in arguing against a Gulf of Aqaba crossing: Even more devastating to the Saudi Arabia theory is the yam suf (Reed Sea) crossing. According to the Bible it occurred at the beginning of the journey shortly after the Israelites set out from Rameses (Ex 12:37; 13:20-14:2; Nm 33:5-8). The Saudi Arabia theory places the yam suf crossing near the end of the journey.21 Gordon Franz says this: Bible geographers who deal with the Exodus take the three encampments from Rameses to the Red Sea, i.e. Succoth, Etham and Migdol, to refer to three days of travel. The Bible does not explicitly say this. Joel McQuitty made an interesting suggestion back in 1986. He suggested that the seven day Feast of Unleavened Bread commemorates the seven days it took to go from Rameses to the Red Sea (1986:103-105; Ex. 13:3,4; 12:33f.; Deut. 16:3; Lev. 23:42-43).22 From that point on in his article, Franz takes it for granted that his seven days scenario is done and dusted. However, this scheme completely falls apart upon closer examination of the timing. The actual schedule argues strongly against a Gulf of Suez crossing and powerfully in favor of a Gulf of Aqaba crossing! Consider the summary account of the Israelite's journeying between Egypt and the crossing: Then the children of Israel moved from Rameses and camped at Succoth. They departed from Succoth and camped at Etham, which is on the edge of the wilderness. They moved from Etham and turned back to Pi Hahiroth, which is east of Baal Zephon; and they camped near Migdol. They departed from before Hahiroth and passed through the midst of the sea. (Num. 33:5-8). This account lists Succoth, Etham, and Pi-Hahiroth as stopover points before the crossing. The most likely crossing point on the Gulf of Suez (between Adabiya and Uyub Musa) is located approximately eighty to ninety miles from where Rameses is believed to have stood. If each stop represents the halting point at the end of a day's travel, that would mean they travelled nearly thirty miles per day. That would be a hard slog, but certainly quite doable. If they took seven days to do it, then they had to travel a mere thirteen miles or so per day. Perfect. A straight-line march from Rameses to the nearest point on the Gulf of Aqaba is 200 miles. Compared with a crossing somewhere along the Gulf of Aqaba, then, a Gulf of Suez crossing seems a more likely prospect. The verdict seems clinched. But wait a minute. It's not as straightforward as a superficial reading might suggest. Let's continue the account in Numbers 33: They departed from before Hahiroth and passed through the midst of the sea into the wilderness, went three days' journey in the Wilderness of Etham, and camped at Marah. They moved from Marah and came to Elim. They moved from Elim and camped by the Red Sea. They moved from the Red Sea and camped in the Wilderness of Sin (vss. 8-11). After crossing the Red Sea they walked for three days to get to Marah, after which Elim alone and a stopover by the Red Sea separated them from the wilderness of Sin (not the same as the wilderness of Sinai). Going by the reasoning just used, that would mean they departed Elim six days after the crossing, making a total of nine days to get all the way from Rameses to the departure from Elim. Add a day for the crossing, and you have ten days. However, notice what Exodus 16:1 says: And they journeyed from Elim, and all the congregation of the children of Israel came to the Wilderness of Sin, which is between Elim and Sinai, on the fifteenth day of the second month after they departed from the land of Egypt (Ex. 16:1). That's thirty days after leaving Rameses, not ten. We must conclude that it often took two or three days to get from one campsite to the next. We have no alternative but to do some intelligent guesswork to figure out the details of the timing. Such deduction leads to the conclusion that a Gulf of Aqaba crossing is completely conceivable in spite of its greater distance from Egypt. Think about it. Imagine ten days transpired between crossing the sea and departing from Elim, which seems a sensible conjecture. That would leave twenty days from departing Rameses to the time they pulled themselves up to safety on the far side of the Gulf of Aqaba. Taking out three days of Sabbath rest (likely coinciding with Succoth, Etham and Pi-hahiroth) would leave seventeen days of walking. (Considerations such as these make nonsense of the position of some that Mount Sinai is to be found three days journey from Egypt.) The trip from Rameses to a logical crossing point on the Gulf of Aqaba, even allowing for a circuitous route, is around 270 miles. That would make an average daily travel rate of sixteen miles. (Compare that with the snail's crawl involved if they took seventeen days to travel ninety miles from Rameses to a Suez crossing.) Could they have kept up such a pace? I recently decided to see how far I could walk in a day. I walked to another town eleven miles away and back again in under six hours. I'm 61 and lead a sedentary lifestyle, and I did not set a cracking pace. True, I could not have repeated it the next day. People who had known nothing but hard physical labor all their lives could easily have covered twenty five miles per day in a forced march on flat ground. The question naturally arises as to whether such a pace could be achieved by many thousands of people with carts and animals in tow, especially if they had to negotiate narrow places or rough terrain on the way. (That they took carts is made clear in Numbers 7:3). Would they not trip over each other? Would not bottlenecks slow down progress dramatically? One doesn't have to be a genius to recognize that a mass of people having to dodge fellow walkers could not make as much progress as an individual. We would be hard pressed to find a better source of information on the question of moving large numbers of people at a rapid pace than the military. After all, we are told that the Israelites marched out of Egypt "in orderly ranks" (Ex. 13:18). Some translations render the Hebrew [chamushim] as "armed"; however, no other example can be found of such a translation of "chamushim", which has a literal meaning something like "in fives". The New Geneva Study Bible comments that it means "Israel went out in military formation, disciplined and prepared". They had been training for this adventure for some time. In the military, a rapid movement of infantry is known as a "forced march". Ulysses S. Grant had this to say about a forced march: I did not believe this possible because of the distance and the condition of the roads, which was bad; besides, troops after a forced march of twenty miles are not in a good condition for fighting the moment they get through (Personal Memoirs, Chapter 28). Twenty miles seems a fair distance to expect an army to travel, but it certainly wouldn't break any military records. Mark Healy describes the line of march of ancient Assyrian armies heading out on campaign, listing the order of procession as, first, the "van" carrying the standards of the gods, followed by the king in his chariot surrounded by his large personal bodyguard and then, in order, the chariotry, the cavalry and the infantry. He adds, Following behind the combat troops came the siege train, supply wagons and assorted camp followers. A number of accounts indicate that such a column could travel 30 miles a day in good going (1991, p. 23-24). Any suggestion that the Israelites could not have maintained a healthy pace on the grounds that progress would have been slowed dramatically by carts and cattle are exposed as nonsense by historically-attested examples such as these. Even more remarkable examples can be found: When Edward the Confessor died on the 5th of January in the year of our Lord, 1066, there were three major claimants to the English throne. Harold Hardrada, King of Norway; William of Normandy and a Saxon Prince named Harold Goodwinson. The Witenagemot declared the latter King immediately, and he was duly crowned. The two losers began recruiting armies, acquiring boats, securing horses and weapons. Hardrada invaded North England on the 20th of September with something like 300 Viking longboats and seized the City of York. Learning of their incursion, Goodwinson immediately marched north and met the Norsemen at Stamford Bridge, annihilating the conquerors and killing Hardrada himself during the battle. Coincidentally, during the course of this foray, the winds in the English Channel shifted, allowing William's Norman fleet to make a landing unopposed on the English Coast where he selected ground near Hastings, positioned his forces and prepared fortifications. Goodwinson hustled back south with his troops, covering the 241 miles in five days and began gathering reinforcements and supplies (MacAllister 2010, p. 4).23 That's nearly fifty miles per day. This tour de force is shown to be more remarkable still when you consider that these troops had reached Stamford Bridge by marching from London - about 160 miles - in four days.24 By the time they went to battle at Hastings they had already fought one major battle and walked 400 miles in a mere nine days. The Israelite ironmen and women would have found walking 270 miles in seventeen to twenty days a piece of cake. Remember; the Israelites were fleeing for their lives from slavery and incensed Egyptians. They would have set a cracking pace, as possibly alluded to in Deuteronomy 16:3. (This verse could, however, be referring to the circumstances of the departure rather than a description of the entire journey.) In sum, the Israelites were in a hurry to put as many miles between Egypt and themselves as possible. A leisurely stroll to the Gulf of Suez simply does not comport with these facts. The very fact that they left in military formation suggests they knew what was coming, and were fully prepared. They were no disorganized rabble but a well-oiled and very fit team of synchronized walkers. Soldiers and young people are one thing, but what about the animals, the elderly, and children ? A couple of explanations can be called on. First, the Scripture tells us that "there was none feeble among His tribes" (Ps. 105:37), and that "their feet did not swell" (Neh. 9:21), suggesting that the otherwise weak and infirm had miraculous help. A second possibility is that the slowpokes rode either donkeys or carts. The Israelites obviously had carts loaded and ready to go when the time came to depart. They certainly didn't carry their tents in backpacks. What about animals? One writer who is a strong supporter of the biblical record seems to fall from grace on this point: A large group of pastoralists moving with their possessions and animals can cover no more than 6 miles in a day, and usually less. The limiting factor is the animals. When the Israelites left Egypt, they had "large droves of livestock, both flocks and herds" (Ex 13:38). Adequate sources of water had to be sought for them along the way and time had to be taken to allow the flocks and herds to graze as they traveled.25 Is the "nomadic pastoralist model" the correct one to apply to the fleeing Israelites? No. Theirs was a different kettle of fish altogether. The better fit here is the drover's model: Cattle drives had to strike a balance between speed and the weight of the cattle. While cattle could be driven as far as 25 miles (40 km) in a single day, they would lose so much weight that they would be hard to sell when they reached the end of the trail. Usually they were taken shorter distances each day, allowed periods to rest and graze both at midday and at night. On average, a herd could maintain a healthy weight moving about 15 miles per day. Such a pace meant that it would take as long as two months to travel from a home ranch to a railhead.26 Maintaining healthy weight was not the primary aim of the fleeing Israelites. They drove the flocks and herds hard; and theirs was undoubtedly the most organized and methodical cattle drive in history. Certainly the largest. As for sheep, information about the maximum distance they could travel in a day at a steady trot seems impossible to find. Before concluding this section, consider this revealing statement in the book of Isaiah: There will be a highway for the remnant of His people who will be left from Assyria, as it was for Israel in the day that he came up from the land of Egypt (11:16). In his commentary on the book of Isaiah, John Watts says, . "highway" means an artificially built up road, not simply a "path" or a "way" (Word Biblical Commentary, Vol. 1, 1985, p. 179). Unless talking about a miraculous creation, this highway would be none other than the King's Highway. It was not just a cow path wending its way across the stony terrain, but was built by Egypt's best engineers and builders; Israel's flight was facilitated by a state-of-the-art highway enabling the carts to go at a cracking pace. Rebutting arguments against a Midian connectionWe have noted the crucial biblical evidence that Mount Sinai is to be found in the land of Midian - the land where Moses lived for forty years and where he pastured Jethro's flocks. Traditionalists argue against the biblical facts on this point in their desire to support tradition. Which is a strange position to take when you remember that today's traditional views are Johnny-come-latelies; earlier traditions place Mount Sinai in Midian. (See Kerkeslager 2000 for a thorough account.) Articles available online that outline the main arguments against a Midianite connection include, • Is Mount Sinai in Saudi Arabia?, by Gordon Franz27 • Problems with Mount Sinai in Saudi Arabia, by Brad Sparks28 • Thoughts on Jabal al-Lawz as the Location of Mount Sinai, by Bryant Wood29 An entire site, Against Jabal al-Lawz,30 is dedicated to debunking the Midian connection. The authors of these articles quite correctly decry the supposed archaeological evidence touted by some as proving that Mount Sinai is to be identified with Jebel al-Lawz. The biblical record makes a Jebel-al-Lawz Sinai most unlikely. However, their claim that they have found "devastating Biblical disproof of Sinai-in-Arabia" (Sparks) is easily shown wanting. The argument goes like this: Exodus 18:27 states that, while the Israelites were camped near Mt. Sinai, Moses sent his Midianite (Saudi Arabian) father-in-law Jethro back to "his own country" of Midian. Clearly, Mt. Sinai and northwestern Saudi Arabia (Midian) were in two different locations. The making of the statement signals the importance of the action, it was not a trivial event or insignificant journey for Jethro to go back to Midian from Mt. Sinai. This incident was repeated about a year hence on a later visit to Mt. Sinai by. Hobab (Numbers 10:29-31). Moses asked him to stay and guide the Israelites to the Promised Land, but he declined, saying he would return to "my own land" (Midian) and "my own people" (Midianites) from Mt. Sinai. He did not want to go on a long journey to Moses' land with Moses' people. Hobab's land (in what is modern Saudi Arabia) was clearly not the same land where they were at (Mt. Sinai) and not the same land where they were going (Canaan), which were national or geopolitical entities spread across a great distance and requiring an expert guide to navigate (Sparks). Franz makes this comment concerning Hobab: "… the text is saying Hobab wants to return to his own land, the place of his birth (Midian), which can only be done by departing from Mount Sinai, because it is outside his homeland." Do the statements by both Jethro and his son, Hobab, show that Mount Sinai must be located in what we know today as the Sinai Peninsula? No way. For one thing, were their argument actually sound (which it isn't), that would still not add any weight to the contention that Mount Sinai must therefore be found in what we call the Sinai Peninsula. Logically, it could be anywhere beyond the "borders" of Midian, even a few meters. Anywhere at all - east, north, or south, not just west. It could still be in modern Saudi Arabia! That Mount Sinai may well have been outside what the ancients would have acknowledged as generally belonging to the Midianites is attested to by the fact that Mount Sinai was in a wilderness (Ex. 19:1) and that the Israelites had to go through the wilderness of Sin (Num. 33:11) to get there. The term "wilderness" (Hebrew, midbar) refers primarily to land not under any particular people's possession. The world's population then was much lower than it is today and as a consequence much land - good land - had not been claimed by anybody and so was not defended against interlopers. If Mount Sinai was in unclaimed land bordering Midian, as seems to be the case, then Jethro could be said to be returning to his land - by Franz's definition - even if it were a mere hop, skip and jump away. If Sergio Rodriguez lived in Tijuana, Mexico, and went to visit family living in San Diego, he would be "returning to his own land" by merely driving back across the border! Let us repeat: the testimony of Hobab in no way scuttles a Saudi Arabian location for Mount Sinai, and in no way supports a Sinai Peninsula location. Furthermore, Franz's assertion that "lands" were "geopolitical entities spread across a great distance" is simply untrue. He has made a classical mistake, taking a specific meaning of a word in modern English and then imposing it onto a foreign word, in this case the Hebrew word, "eretz". The truth is that "eretz" has a broad semantic range (as, in fact, does the English word "land"). At one end of the spectrum it can mean "planet earth", as in Genesis 1:1, while at the other end it can be very localized, meaning something akin to "my patch of ground" as distinct from "your patch of ground". True, eretz does appear to have been used at times in much the same way as our word "country" or "nation", in which borders and sovereignty were respected. Towards the end of the Israelites' wanderings, Moses asked permission of the king of Edom to ". pass through your country [eretz]" (Num. 20:17). In many cases, though, boundaries were fluid affairs, being defined by the caprice of a ruler rather than by treaty; whatever a given king was willing to defend established the de facto border. The next king might have had a different idea. And, as just noted, some extensive areas, such as the Sinai Peninsula, were claimed and defended by no one. Furthermore, huge areas were inhabited by nomadic peoples whose "borders" moved with them. In sum, the geopolitical scene in Moses' day was conceptually different from our time. Compared with our neat patchwork quilt of nations with semi-permanent borders, theirs was a dog's breakfast of constantly-changing "lands". With that in mind, expressions as seemingly simple as "go to my land" must be read with caution. What Hobab had in mind may be quite different from what Gordon Franz imagines. Which leads to the next point. "Eretz" can refer to a very limited patch of turf. Although no biblical passage can be found where the idea is expressed, if the script of a Western movie was translated into ancient Hebrew, then the word used for "land" in the expression "Get off my land" would probably be "eretz". While Abraham was wandering around the "eretz of Canaan" he became friendly with Abimelech, king of a mere city state known as Gerar. Abimelech took a liking to Abraham and said to him, See, my land [eretz] is before you; dwell where it pleases you (Gen. 20:15). Here we have indisputable reference to a "land [Gerar] within a land (Canaan)". Likewise, we read about the "land of Goshen" (Gen 45:10 et al) as a "land" within the "land" of Egypt. Read Zechariah 14:10 and Genesis 13:5-12 for examples of lands within lands like wheels within wheels. By the same token, Jethro and Hobab may well have been referring to their city or region as a "land" within the "land of Midian". Some historians consider that Midian could not be considered a "country" in our sense of the word at all, but an amphictyony - an alliance of independent tribes that may be separated from each other geographically, each having its own "land", possibly only hundreds of square miles in area but part of a larger "confederacy of Midian" living in "the land of Midian (Ex. 2:15).31 We can go further. We must remember that words are merely symbols of ideas, or concepts. Common concepts are often expressed in different languages in very different ways. One could fill a book with examples, but let us consider one random one. When Judas felt some remorse over betraying Jesus for money, he went to the priests to return it. Their response to him was, as translated literally in the NKJV, "What is that to us? You see to it" (Matt. 27:4). The first sentence makes sense to us, but the second doesn't. The closest functional equivalent in modern English would be something like, "That's not our problem, that's your problem/lookout". An extremely common term in modern English is "to go home". When you visit relatives, you will no doubt say to them when you feel it's time to leave that, "It's time we went home", whether "home" is only a few blocks away or hundreds of miles removed. Now, do we imagine that the Israelites had no way of expressing the concept of "going home"? Of course they did. English translations of the Old Testament use the term "go home" in a handful of places, rendering it from a few different Hebrew expressions, such as, literally, "go to one's tent" (Jdg. 19:9), "go to one's house"(1 Sam 24:22) and "go to one's place" (2 Chron. 25:10). If going home required more than a walk down the street or over the nearby hill, the idea may well have been expressed by "go to one's eretz ". Moses could be said to have merely "sent Jethro home" with his blessing. Hobab could have been saying nothing more than, "Thanks for the offer to go with you Moses, but I think right now I would prefer to go home where I belong". The phrase "one's own land" certainly can, and often does, refer to what we would call today "one's country". But in many cases where we read about people returning to "their land" the concept being expressed would be best rendered in English by "going home", without any particular attention being paid to geopolitical boundaries. We have belabored this point because Franz and others see it as the near-ultimate proof against a Saudi Arabian setting for Mount Sinai. The supposedly "devastating disproof" of the Sinai-in-Midian proposition, based on specious reasoning, carries no weight at all. Franz replaces a plain reading of Exodus 3 with a far-fetched alternative interpretation. He suggests that Moses, while living in Midian, had heard a rumor that Pharaoh had died, and that he was desperate to get news of his people's plight in Egypt. What better way to eavesdrop on the gossip than to head for Egypt. Fearing he was still a "dead man walking" in the eyes of the Egyptians, he decided to pass himself off as an old shepherd by taking Jethro's flock as a cover for his reconnaissance activities. Afraid to enter Egypt, he headed for the mountain known as Jebel sin Bishar (the authentic Mount Sinai according to Franz - he, too, rejects the traditional location), located about 40 miles southeast of the modern city of Suez. Franz tries to persuade us that a trip to this location with a flock of sheep would be a perfectly normal kind of trip for a shepherd. He assures us that, It is not unusual for Bedouin shepherds to go long distances to find pasture for their flocks. I have met Bedouin shepherds who come from the Beersheva region with their flocks north of Jerusalem, a distance of over 70 miles. Trouble is, even taking Moses' starting point as being right in the north of Midian, the trip to Franz's Mount Sinai is 135 miles, nearly double the distance he mentions. Furthermore, its location in central-west Sinai Peninsula takes it far from any gossip-ridden Egyptian tavern or caravan route. Franz himself argues strongly that the Sinai Peninsula at that time was not Egyptian territory and was sparsely settled, going so far as to say that "the Israelites would have found Sinai 'quite empty' when they left Egypt". Forget it, Mr. Franz. Mount Sinai, where Moses took his father-in-law's flock, was in or bordering on Midian, as Exodus 3 suggests. Aaron comes to meet MosesFinally, Franz notes the statement in Exodus 4:27 that seems to suggest that Aaron came to meet Moses at Mount Sinai while he, Moses, was en route back to Egypt to rescue the Israelites: And the Lord said to Aaron, "Go into the wilderness to meet Moses." So he went and met him on the mountain of God, and kissed him. Note the context: Moses appears to have been somewhere between Midian and Egypt when Aaron met him at Mount Sinai. Franz comments: The impression from the text is that Moses was almost back to Egypt when he met Aaron and not Aaron travelling all the way to Midian to meet Moses. Seems quite conclusive, n'est ce pas? Not at all. Let the New Geneva Study Bible help set the record straight. It comments that, "In Hebrew narrative style, this statement takes the reader back in time to explain Aaron's meeting with Moses before Moses left Sinai" (emphasis mine). That is, before Moses left Sinai on the occasion God spoke to him there at the burning bush. It's a flashback. This Bible commentator, whoever he may be, undoubtedly accepts the traditional southern Sinai Peninsula location for Mount Sinai, but his explanatory note applies equally well if referring to a Midianite Sinai. Frankly, to suggest that Moses took a major detour en route from Midian to Egypt to climb a high mountain with his wife and child makes no sense at all. It makes a lot of sense to envisage God telling Aaron to go to Mount Sinai [in Midian] for the purpose of confirming in Moses' mind that God was involved in this scary, faith-testing affair. The episode of the burning bush would have been impressive enough; how much more impressive and confidence-building for Moses if Aaron immediately arrived on the scene with confirmation from God of His intentions. Before we leave discussion of arguments for and against a Midianite location for Mount Sinai for good, mention should be made of a rather bizarre usage of the "Midianite connection" to support locating Mount Sinai in the Negev region of modern Israel. For a discussion, see "The case of the strange Midianite connection". Chariots could not negotiate Sinai terrainOne argument used to deny a Gulf of Aqaba crossing relates to the statement that the Egyptian army pursued the Israelites with their chariots (Ex. 14:7). I. E. Harding makes this comment: Even ignoring the biblical evidence placing the crossing at the Ballah Lake, Egyptian chariots could not have possibly traveled upon the et-Tih, for the roughness of the terrain would utterly destroy them, and the only road Egyptian chariots traveled on was the coastal "Ways of Horus", which the Israelites were explicitly told to avoid (Ex 13:17).32 How true is this contention? Egyptian chariots were used in numerous places over the centuries. If they were so fragile that they could not negotiate the flat stony terrain of the Sinai Peninsula close to home, what use were they? Why have a chariot regiment if it was restricted to fighting along one route? Egyptian chariots fought in the Battle of Carchemish, around 700 miles from Egypt (Jer. 46:9). Are we to believe that the Egyptians found stone-free, chariot-friendly terrain all the way? Maybe chariots were transported on robust carts to the battlefield. One cannot help but wonder if Harding is making an assertion about which he has no certain knowledge. How can he be so sure that Egyptian chariots, at that moment in history, were incapable of negotiating the Red Sea Wilderness Road? It was a heavily-trafficked road, being the final leg of the incense route from southern Arabia to Egypt. Historians believe the donkey, not the camel, was the primary beast of burden at that time; it is inconceivable that these important trading routes were not maintained sufficiently to provide plain sailing for donkey-drawn carts and, hence, chariots.

16 Essay about the phenomenon of Lessepsian Migration [Back] 17 Catholic Encyclopedia [Back] 18 Wyatt Archeological Research [Back] 19 For a good starting point for exposing Ron Wyatt's claims, see Tentmaker [Back] 20 New King James Version [Back] 21 Thoughts on Jebel al-Lawz as the Location of Mount Sinai [Back] 22 The Chronology from Rameses to the Red Sea [Back] 23 ASOR Newsletter, Winter 2010 (pdf) [Back] 24 Harold Godwinson [Back] 25 Thoughts on Jebel al-Lawz as the Location of Mount Sinai [Back] 26 Cattle drives in the United States [Back] 27 Is Mount Sinai in Saudi Arabia [Back] 28 PROBLEMS WITH MT. SINAI IN SAUDI ARABIA [Back] 29 Thoughts on Jebel al-Lawz as the Location of Mount Sinai [Back] 30 Against Jebel al-Lawz [Back] 31 The Catholic Encyclopedia, while distancing itself from the original amphictyonic theory of Haupt, says of the Midianites that, "Madianites is, then, to be regarded as the generic name of an immense tribe divided into several clans of which we know at least some of the names". [Back] |

|

|

|

Dawn to Dusk publications |

Other printed material |

On the Web |

|

|

|

|

| Edited and expanded copies of this article, in reprint pamphlet form, can be purchased by going to the reprints order page. As well as reprints, Dawn to Dusk offers books in printed form and on CD-ROM. We mail to anywhere in the world! For more information on what is available, prices, and how to order, click the icon. |