|

Marvels and mysteries of the Sinaitic Covenant |

|

|

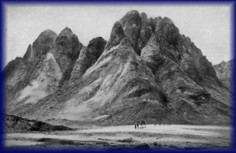

EVERY BIBLE STUDENT KNOWS THAT THE COVENANT God made with Israel is dead or, at best, is dying. Hours before His death, Jesus proclaimed the imminence of a new covenant: Likewise He also took the cup after supper, saying, "This cup is the new covenant in My blood, which is shed for you" (Luke 22:20). The coming of a new covenant implies the previous existence of an old covenant. An oft-debated question is whether this new covenant immediately and completely replaced the old or whether the two exist side-by-side for a period of time, with the new gradually replacing the old. Hebrews 8:13 suggests the latter: In that He says, "A new covenant," He has made the first obsolete. Now what is becoming obsolete and growing old is ready to vanish away. Nobody can doubt that "the first" covenant, the "old covenant", is one and the same as the covenant struck between the Holy One of Israel and His people at Mount Sinai. Whether that covenant is dead or moribund is not of interest to us here. What concerns us is the question of why that covenant was ever made in the first place. Does the Bible present that covenant in a positive light or negative light; was it a good covenant or a bad covenant? What is the truth of the matter? An even older covenantTo get some perspective on this matter we need to recognize that the "old covenant" made at Sinai was actually new at the time it was made by comparison with an even older covenant: On the same day the Lord made a covenant with Abram, saying: "To your descendants I have given this land, from the river of Egypt to the great river, the River Euphrates" (Gen. 15:18). This covenant, known variously as the "Abrahamic covenant" or "the patriarchal covenant" was expanded over time to include a number of other promises, such as God's promise that "I will be their God" (Gen. 17:8), and "you shall be My people" (Lev. 26:12), and, above all, that through one of Abraham's descendants "all the nations of the earth shall be blessed" (Gen. 22:18) - the most significant promise ever made by anybody in all of the history of the universe. This fundamental covenant is described as "everlasting" in passages such as Genesis 17:7. Numerous Old Testament prophecies point to the ultimate consummation of all the promises God made in this covenant. Their ultimate fulfillment is made possible because of the past, present, and future work of the promised descendant of Abraham - Jesus Christ. Few realize that Jesus came to make this covenant "stick": Now I say that Jesus Christ has become a servant to the circumcision for the truth of God, to confirm the promises made to the fathers (Rom. 15:8). The importance of this covenant cannot be exaggerated. Though few Christians realize it, the hope of eternal life made available through faith in Jesus Christ is contained within it. Abraham was promised eternal inheritance of the Promised Land (Gen. 17:8), a promise that requires his resurrection for its fulfilment. Abraham's spiritual seed share in the same promise. God remembers this covenant made with Abraham "for a thousand generations" (Ps. 105:8-9). How does the intervening Sinaitic Covenant fit into this great scheme of things? Nowhere in the Old Testament is it described as an "everlasting" covenant. Nowhere does God declare that He will remember it "for a thousand generations". The Old Testament foretold its demise, even if only by implication: Behold, the days are coming, says the Lord , when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah - not according to the covenant that I made with their fathers in the day that I took them by the hand to lead them out of the land of Egypt, My covenant which they broke, though I was a husband to them, says the Lord . (Jer. 31:31-32). The specific ancient covenant that is viewed in a negative light here is not the covenant made with Abraham but the one made with Israel at Mount Sinai. The apostle Paul, describing the old covenant under the moniker of "the law", tells us that, So that the law was our custodian until Christ came, that we might be justified by faith (Gal. 3:24, RSV). The covenant instituted at Sinai, by contrast with the eternal Abrahamic covenant, is shown in both Old and New Testaments to have been temporary in nature. But again, what was it all about? Many commentators talk nonsense concerning the Sinaitic Covenant, insisting that it provided the means by which Israel became God's chosen people and "one nation under God". The Illustrated Bible Dictionary gives a typical example: The covenant made here between God and the people played a major role in binding the tribes together and molding them into one nation serving one God (Sinai, p. 1461). Such ideas ignore plain testimony that Israel already was God's people (Ex. 5:1 et. al.) and He already was their God (Ex. 3:18 et. al.) well before arriving at Mount Sinai, just as God had promised to Abraham. The covenant made at Sinai had quite a different purpose from establishing Israel as God's people or nation. Sinai promises. and conditionsWhat does the Old Testament - more specifically, the book of Exodus - tell us about the purpose of the old covenant? Nothing; at least, not explicitly. Nowhere does it say, "Because. therefore.". It does, however, outline the promises made by God as His side of the "deal": You have seen what I did to the Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles' wings and brought you to Myself. Now therefore, if you will indeed obey My voice and keep My covenant, then you shall be a special treasure to Me above all people; for all the earth is Mine. And you shall be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. These are the words which you shall speak to the children of Israel (Ex. 19:4-6). Now for a vital point. Each one of these promises - special treasure status, kingdom of priests status, and holy nation status - can be seen as elaborations of the fundamental thrust of the Abrahamic covenant to the effect that Israel would be God's people, and its corollary. Furthermore, the fine print of the covenant makes plain that this covenant, by extension, includes another fundamental feature of the Abrahamic covenant: inheritance of the land: Little by little I will drive them out from before you, until you have increased, and you inherit the land (23:30). The covenant cut at Sinai seems to cover much of the same territory as the Abrahamic covenant - people-of-God status and inheritance of the Promised Land. But wait: we have seen that these same promises had been active even while Israel was in Egyptian bondage. Even the promise that they would inherit the land promised under the Abrahamic covenant can be seen as "under development" long before arriving at Sinai: Therefore say to the children of Israel: "I am the Lord ; I will bring you out from under the burdens of the Egyptians, I will rescue you from their bondage, and I will redeem you with an outstretched arm and with great judgments. I will take you as My people, and I will be your God. Then you shall know that I am the Lord your God who brings you out from under the burdens of the Egyptians. And I will bring you into the land which I swore to give to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; and I will give it to you as a heritage: I am the Lord " (Ex. 6:6-8). They already were God's people, because of which God would shortly "take them" as His people by rescuing them. We have here quite a mystery: the Sinaitic Covenant seems to reiterate and amplify promises which had already begun to be fulfilled in a major way. Why have a second covenant merely to restate promises made in a previous covenant? At first sight, a simple and elegant solution would be to view this covenant cut at Sinai as a ratification of the Abrahamic covenant, a formalization, if you will, of something previously agreed upon by "handshake". That solution will not do. For starters, the Abrahamic covenant was a fully formalized affair; read Genesis 15. Secondly, the Sinaitic Covenant is described in generally negative terms in both Old and New Testaments, as seen in a number of Scriptures such as those cited above (Jer. 31:31-32 & Gal. 3:24) and in the circumstances of the making of the old covenant itself. By contrast with the happy context of all the Abrahamic promises, the promises made at Sinai were set in a fearful, terrifying atmosphere. Any who touched the mountain would be stoned or shot with arrows (Ex. 19:12-13). The sights and sounds of God's descent onto the mountain were so dreadful the people "trembled and stood afar off" (Ex 20:18). Here we have not the cork-popping of a wedding party but the bone-rattling of sheer fear. Finally, a totally new element appears in this covenant compared with the original Abrahamic: conditions. The Abrahamic covenant contained no conditions. Read again the summary of the covenant in Exodus 19:4-6 quoted above. These verses add something new. Israel had to fulfill a major obligation towards God if they hoped to enjoy the promised blessings; "obey My voice and keep My covenant". The "thing" that they had to obey was the law that He outlined in chapter 20 and beyond, the whole being summarized in the famous Ten Commandments. God's ancient law served as terms, or conditions, that Israel must fulfill if they were to enjoy the blessings promised. We have here quite a mystery. God promised all these blessings to Abraham without mentioning any conditions. At Sinai, the promises were restated under threatening conditions and with strings attached. What is going on? Note one feature of the Abrahamic covenant that does not rate a mention in Exodus 19 - "In your seed all the nations of the earth shall be blessed. " (Gen. 22:18). Can the failure to mention this noblest of all Abrahamic promises in the Sinaitic Covenant's fine print be a case of oversight on God's part? Ridiculous. Or of a transmission error in the text? Not likely. The Sinaitic Covenant, it seems, is a restatement of sorts of the "material" aspects of the promises to Abraham, now made conditional, while the "spiritual" promise of a "seed of blessing" is conspicuously absent. In short, the Sinaitic Covenant is not good news; something dreadful, albeit just and right, happened in the shadow of Har Kodesh. The book of Exodus, we repeat, does not explain what is going on. As a result, even if the Israelites of that time understood what was going on, later generations appear to have missed the point. Sinai was a sad, bad day in Israel's history; later generations saw it as their ultimate triumph. Misunderstanding the purpose and reason for the covenant made at Mount Sinai set the scene for the huge problems faced in the early church over the issue of Gentile admission to the congregation of the faithful. A little history lessonBefore we seek to New Testament insights to clear up the puzzle, think about this amazing verse: For who, having heard, rebelled? Indeed, was it not all who came out of Egypt, led by Moses?(Heb. 3:16). Please read that again. Rebellion against human leaders is considered a serious offence. Against God, it amounts to the ultimate iniquity. Then consider this summary statement concerning the Israelites whom God delivered from slavery for the purpose of giving them a land flowing with milk and honey: Therefore I was angry with that generation, and said, "They always go astray in their heart, and they have not known My ways" (Heb. 3:10). You can hardly imagine a more scathing indictment than that. God had released these people from indescribable suffering, annihilated their tormentor's army before their very eyes, and made them participants in the most dramatic miracle in human history. They had seen the walls of water towering overhead as they made their way through the Red Sea and had watched them collapse on Pharaoh's army. Before all that, they had witnessed the heart-stopping plagues God had brought on the Egyptians over a period of months; they had been thrust out of Egypt with arms laden with silver and gold and jewelry and had been guided in the journey towards the Gulf of Aqaba by a pillar of cloud and fire. How did they show their gratitude towards God? Our fathers in Egypt did not understand Your wonders; they did not remember the multitude of Your mercies, but rebelled by the sea - the Red Sea (Ps. 106:7). The Soncino translation renders "did not understand" as "gave no heed", suggesting a considerably more ignoble impulse to their deeds. Surely we live in as ungodly an age as has disgraced the face of the planet, but even we must be taken aback by Israel's glaring unbelief at the edge of the Red Sea: Then they said to Moses, "Because there were no graves in Egypt, have you taken us away to die in the wilderness? Why have you so dealt with us, to bring us up out of Egypt? Is this not the word that we told you in Egypt, saying, 'Let us alone that we may serve the Egyptians?' For it would have been better for us to serve the Egyptians than that we should die in the wilderness" (Ex. 14:11-12). In the short space of six weeks between their departure from Egypt and their arrival at Har Kodesh, the Israelites caused God great grief and anger on six separate occasions (Num. 14:22: the other four occurred at Sinai or later). What insufferable ingrates! Paul tellsRarely in the annals of human history have so many shown such ingratitude towards their gracious benefactor so consistently. The generation that left Egypt was "low class" in every conceivable nuance of the term. With that as backdrop we can better grasp the significance of Paul's statements about what happened at Mount Sinai: What purpose then does the law serve? It was added because of transgressions, till the Seed should come to [in] whom the promise was made (Gal. 3:19). Paul uses the term "the law" here as a euphemism (or, more properly, a metonym1) for "the old covenant". (In Galatians he uses the metonym "promise/s" to stand for the Abrahamic covenant.) In delivering Israel from Egypt, God was actively fulfilling the promises made to Abraham, an act which should have caused delirious joy in the Israelite camp. The implication is that all the blessings promised to Abraham's descendants would shortly be ushered in, including the promise that "in Abraham's seed" they, as the first of the nations, would "be blessed". (We'll see in a moment what that means.) Instead of undying gratitude, the Israelites responded with bellyaching and rebellion. So God introduced a codicil into the Abrahamic covenant - the Sinaitic Covenant. The Sinaitic Covenant was laid down as an amendment, not to the content, but to the time of fulfillment of all the blessings of the Abrahamic covenant. The old covenant was a punitive covenant, strapped alongside the Abrahamic covenant, that called for a postponing of the full and complete benefits of the Abrahamic covenant. The postponement came to an end when the promised seed, Jesus Christ, came. At that time the new covenant renewed the patriarchal promises. Why those promises still have not been consummated cannot be dealt with here. The Sinaitic codicil did not postpone all the Abrahamic promises in full. Not at all. The Sinaitic Covenant allowed for Israel to enter the Promised Land - with the threat of losing it should they continue in their rebellious ways (Lev. 18:26-28) - to prosper in their ways, and to set an example to other nations of God's way in action. The Sinaitic Covenant limited the degree of fulfillment of the majority of the Abrahamic promises as long as it stayed in effect. And it put a near stranglehold on one particular promise. In the book of Galatians, Paul labored to correct the current misunderstanding of his fellow countrymen as to the meaning of the Sinaitic Covenant, which they misinterpreted as Israel's greatest gift from God, and the events at Mount Sinai as its moment of greatest glory. The truth is, the Sinaitic Covenant cut Israel off from access to the most important promise of all - the "blessing" made possible by Abraham's one seed, Jesus Christ. They were shut off from believing/saving faith (Gal. 3:23) made possible through the indwelling Holy Spirit. The gift of the Holy Spirit was part of the promised blessing made to Abraham to be fulfilled "in his seed" (Gal. 3:14). The Sinaitic Covenant postponed the pouring out of the Holy Spirit upon "all nations", including Israel, until after the promised seed had come. In this article we have barely scratched the surface of this important topic. It is dealt with in considerable detail in the Dawn to Dusk book "Shechem to Calvary: The Story of the Covenants".

1A term describing the use of the name of one thing for that of another to which it has some logical relation, as "sceptre" for "sovereignty" or "the bottle" for "strong drink" (Macquarie Dictionary). |

|

|

|

Dawn to Dusk publications |

Other printed material |

On the Web |

|

|

| Edited and expanded copies of this article, in reprint pamphlet form, can be purchased by going to the reprints order page. As well as reprints, Dawn to Dusk offers books in printed form and on CD-ROM. We mail to anywhere in the world! For more information on what is available, prices, and how to order, click the icon. |