|

Mt Sinai, Kadesh Barnea, and the Promised Land Part One Posted: 14th October, 2012 |

|

|

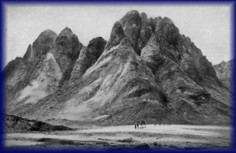

Almost everyone admits that an Exodus occurred. But the details of the journey are presented in such a way that relating them either chronologically or geographically to known historical data is indeed difficult. Yehuda Radday, A Bible Scholar Looks at BAR 's Coverage of the Exodus DIFFICULT, INDEED. This paper, however, attempts to provide a reconstruction of Israel's movements after departing from Mount Sinai that satisfies the biblical data and is contradicted by none. Only a fool would proclaim, “Eureka, I've done it”. The data is so complex and our ignorance of ancient place names so profound that even a thorough analysis risks coming to grief on one overlooked point. Radday goes so far as to suggest that, “There is thus little value in searching for these stations on the map. One may as well try to find Somewhere Over-The-Rainbow” (1982). Try telling that to Sherlock Holmes. He would surely reject the notion that the quest is a pursuit of a will-o-the-wisp. After all, we have established that Israel's journeys took them into ancient Midian, and we have a clear bead on one location mentioned on the route of their journey — Ezion Geber (Num. 33:35). Add a known starting point and a known end point, and you're half way there. The difficulty of tracking Israel's movements will obviously be compounded if one seeks to build on a faulty foundation. Stop and think; if you start with a wrong location for Mount Sinai, then how can you expect the data to make any sense? That is the problem confronting those who hold to the traditional identification of Jebel Musa1 as the holy mount; they're lost from the outset. We will make no attempt here to compare “our” reconstruction with the dozen or so other reconstructions offered for the route of the Exodus from Egypt to Sinai and from there to the Promised Land. The sole exception will be to occasionally compare the scenario presented here with the orthodox view just mentioned, according to which Mount Sinai is equated with Jebel Musa in the south of the Sinai Peninsula, while Kadesh Barnea is equated with Ain el-Qudeirat2 in the north, roughly 40 miles south of the modern, and infamous, border town, Rafah. Until the arrival of Google Earth, students of the Exodus were severely hampered in their ability to follow potential paths in any kind of intelligent fashion. Small scale atlas maps provide little help to the sleuth. We need the detailed topographic data that Google Earth provides. Without access to Google Earth, the chances of cracking the Exodus code would be minimal. All thanks to John Hanke. We will be focusing primarily on what many may consider dry facts of history rather than on seeking to tease out lessons for life or on exposing the glory of God; may we remember, however, that every step of Israel's odyssey was either planned or foreseen by God. In short, Israel's wilderness experience needs to be viewed as a work of God, on a par with the calling of Abraham, the Exodus, the conquest of the Canaanites, the glories of Solomon, the exile of Israel and Judah, and even the Creation. Our study of this topic will benefit greatly from humbly acknowledging God's intimate involvement in this momentous, protracted event. Everything God does is worth infinitely more than the sum total of all human achievements. Much of what He did eludes our immediate comprehension; the problem lies with our innate superficiality and not with His wisdom. This article has the limited purpose of making sense of the biblical data and so, by extension, to making a contribution to the cause of Scripture's credibility. Rejectionists ridicule the biblical narrative as riddled with error. Oh that they would cease from their stubbornness and approach the Word of God with fear and trembling; then they would see and sing God's praises rather than continuing to stumble in the dark. Golgotha hill is of infinitely more significance than towering Mount Sinai, and Jesus' short walk to Calvary of immeasurably greater moment than Israel's forty years wilderness march. Nevertheless, after the atoning and saving work of the only Son of God, the redemption of Israel from Egypt and her eventual safe arrival in the land promised to Abraham's seed must go down as the ultimate historical event. God remembers His covenant with Abraham “for a thousand generations” (Ps. 105:8); Christendom may have lost sight of the permanent role of Israel in the divine plan, but the Holy One of Israel, the Father of Jesus Christ, has not. Kadesh BarneaWe shall begin with a critical aspect of the post-Sinai narrative — the significance of Kadesh Barnea. We will get to the location of Kadesh Barnea later; for the moment we are concerned merely with establishing some basic facts about the place. Scripture shines a bright spotlight on this place. Deuteronomy 1:19 presents it as Israel's most important port of call between Mount Sinai and the Holy Land: So we departed from Horeb [Mount Sinai], and went through all that great and terrible wilderness which you saw on the way to the mountains of the Amorites3, as the Lord our God had commanded us. Then we came to Kadesh Barnea. It would appear that they arrived there about twelve months after departing Mount Sinai, two years after leaving Egypt. From here, a mere stone's throw from the land of milk and honey that God had promised, over four hundred years earlier, to give to Abraham's seed as an everlasting inheritance, the Israelites were to surge in and seize their inheritance. Moses continued: You have come to the mountains of the Amorites, which the Lord our God is giving us. Look, the Lord your God has set the land before you; go up and possess it… (vss.20-21). But then, disaster struck. When the spies Moses had sent to reconnoiter the land returned, they spoiled their glowing report of its superb assets with fearful accounts of the prowess and overwhelming strength of its inhabitants, many of whom were so tall the spies felt like grasshoppers by comparison (Num. 13). The people felt so sorry for themselves they refused to budge (Num. 14). At that point, God postponed the conquest, sentencing the entire nation to a total of forty years of rough country living, during which time every person who had been over the age of twenty upon departing from Egypt would die (Num 14:26-35). Cut to the quick by the rebuke, the Israelites tried to convince God to retract the divine decree by marching out to do battle with the local natives. The result was disastrous; without God's assistance, the attempt was doomed and abject defeat was certain (Num 14:44-45). Ahead of them lay thirty-eight more years of sleeping in tents in unfamiliar surroundings skirting around the edge of their homeland. Many of those years were to be spent in Kadesh Barnea. The Bible doesn't give enough information to figure out exactly what Kadesh Barnea was — a city or a district. In fact, the same questions hold true for most, if not all, of the stations of the Exodus. Commonsense suggests that any attempt on the part of possibly two million out-of-towners to set up camp on the edge of a city would have provoked a swift response. It could be argued that after the destruction of the entire Egyptian army and the annihilation of the Amalekites at Rephidim, nobody would have dared attack Israel. Indeed, the fear factor could account for the lack of molestation the Israelites experienced during their journeys. That said, however, it is hard to imagine anybody putting out the welcome mat for a horde of foreigners setting up shop in their backyard. Exactly how long they spent at Kadesh Barnea remains moot. Most Christian commentators take Deuteronomy 2:14 to suggest a thirty-eight-year-long stopover: And the time we took to come from Kadesh Barnea until we crossed over the Valley of the Zered was thirty-eight years… This ambiguous statement, made shortly before the conquest, could be taken to suggest a thirty-eight-year stopover. Numbers 9:22, however, suggests otherwise: Whether it was two days, a month, or a year that the cloud remained above the tabernacle, the children of Israel would remain encamped and not journey; but when it was taken up, they would journey. This passage implies that they spent a year or more at a number of locations. If that were the case, simple arithmetic tells us they could not have remained at Kadesh Barnea for thirty-eight years, bearing in mind that they spent the first twelve months of the forty years at Mount Sinai. The passage, recounting events shortly before entering the Promised Land, makes more sense if taken to mean that thirty-eight years had passed since they had arrived at Kadesh Barnea. Jewish students take a different tack, taking their cue from Deuteronomy 1:46: So you remained in Kadesh many days, according to the days that you spent there. Taking the highly-influential medieval French rabbi, Rashi, as his source, Scherman interprets “according to the days that you spent there” to mean that they spent as much time there as they did at all other places combined (1993, p. 947) . Thus, they spent a total of nineteen years at Kadesh Barnea. Makes sense, doesn't it? They spent years at some of the other stopover points, too. Another verse supports this notion. Immediately after the statement that the Israelites “remained in Kadesh many days”, Moses adds, Then we turned and journeyed into the wilderness of the Way of the Red Sea, as the Lord spoke to me, and we skirted Mount Seir for many days (Deut. 2:1). “Many days” in Kadesh Barnea and “many days” skirting around Mount Seir; it makes no sense to interpret the first “many days” as thirty-eight years and the latter as, well… many days. More than one KadeshWe need to remove an obstacle upon which a surprising number of scholars stub their toes — treating two separate places sharing the same name as if they were one place. Numbers 33 provides a list of stopover points all the way from Egypt to the Promised Land. Everybody seems to agree that this list is not a complete catalogue of every place they camped at over the course of forty years but of places where they stayed for an extended period of time, and where the tabernacle was set up and the priests ministered. After leaving Mount Sinai, twenty stations are listed, followed by, They moved from Ezion Geber and camped in the Wilderness of Zin, which is Kadesh (vs. 36). The NIV renders the verse this way: “They left Ezion Geber and camped at Kadesh, in the Desert of Zin”. One could certainly be forgiven for taking this Kadesh to be one and the same as the Kadesh Barnea already discussed. A read of Numbers 13 and 14, which speak unmistakably of events that occurred at Kadesh Barnea, shows that it was sometimes referred to as simply “Kadesh” (13:26). And since no other Kadesh is referred to in Numbers 33 before the Kadesh mentioned in verse 36, it makes sense that this Kadesh is the same as the Kadesh Barnea spoken of in earlier chapters of Numbers. But it isn't; it's a different Kadesh. Let us marshal the evidence showing that they are two different places. (Numbers 34:3 seems to suggest that the Wilderness of Zin is to be identified with at least part, and maybe all, of the Arabah; we should be looking for Kadesh in the Arabah.) To begin with, note the natural sequence in Numbers. Chapters 13 and 14 cover in some detail a few things that occurred when the Israelites were staying at Kadesh Barnea in the very earliest period of their sojourn, with special emphasis on the fateful spying episode and its aftermath. The fourteenth chapter ends on another disastrous note — the doomed attempt to begin the conquest. Numbers 15 through 19 detail other intriguing events that occurred in the wilderness together with an elaboration of various miscellaneous laws. Then you come to chapter twenty, where we read, Then the children of Israel, the whole congregation, came into the Wilderness of Zin in the first month, and the people stayed in Kadesh; and Miriam died there and was buried there (vs. 1). The most natural reading suggests that what is recounted here comes after the events of chapters 13 and 14. Verses 2-5 report on a terrible clamor raised by the people about the wretchedness of the place and its lack of water. Logic suggests that if this were the same place as Kadesh Barnea spoken of in chapters 13 and 14, the water deficiency would have been the first thing spoken of back in those chapters. Furthermore — and this is compelling — while at this Kadesh, plans were made to enter and possess the Promised Land. Moses sent a letter to the king of Edom asking for safe passage through their land, which request was denied. The next chapter outlines the final leg of their journey past Moab to the very brink of the Promised Land, with a couple of significant battles on the way. In sum, these chapters, set at Kadesh, refer to a very late stage of their forty year pilgrimage, while chapters 13 and 14, set in Kadesh Barnea, deal with the earliest phase of their wanderings. They are two different places. Next, that the two Kadeshes are found in different regions is strongly implied. Speaking of the return of the spies to Kadesh Barnea at the beginning of the forty years we are told that, Now they [the spies] departed and came back to Moses and Aaron and all the congregation of the children of Israel in the Wilderness of Paran, at Kadesh… Kadesh Barnea is located in the Wilderness of Paran. (No external sources provide any help in locating Paran. Bible maps place it near Ain el-Qudeirat in the Sinai Peninsula due to preconceived notions about the location of Kadesh Barnea.) The other Kadesh, however, is located in the wilderness of Zin (see above, Num. 20:1). Although it is possible that Zin and Paran are two names for the same area, we propose that they are two different wildernesses, supporting the idea that you have two different Kadeshes in two different places. To summarize thus far, let us quote Scherman's comment on Num. 33:36: This is not the Kadesh of the spies, for that was in the Wilderness of Paran… The arrival at the Kadesh of this verse occurred on Rosh Chodesh Nissan of the fortieth year from the Exodus. It was here that Miriam died and where it was decreed that Moses and Aaron would not enter the land (p. 921). Admittedly, the argument that we are dealing with two separate Kadeshes faces a problem. Put very simply, it is this: if the Kadesh spoken of in Numbers 33:36 is a stopover at the end of the wilderness wanderings, and is not the same as the Kadesh Barnea of spies infamy, then why, pray tell, is Kadesh Barnea not listed earlier in the chapter? One conclusion alone is possible: it is listed, but under a different name. That a place can have more than one name should come as no surprise — which is why Paran and Zin could be taken as two names for the same place. People over sixty today have no problem recognizing that Saigon and Ho Chi Minh City are one and the same. And nobody would be confused when someone refers to Chicago as “The Windy City”. Being known by more than one name at a time appears to be common in the ancient Near East and Egypt. The city the Greeks knew as Thebes was known as “Waset” to the Egyptians for many centuries, and then later took the name of “niwt-imn” (No Amon in Nahum 3:8). Its earlier name was undoubtedly used by many for a long time. Krahmalkov reports concerning a major Moabite city that, “Dibon and Qarho seem to have been used interchangeably as names for the city” (1994). So which of the stations mentioned in Numbers 33 is the same as Kadesh Barnea? Jewish tradition associates it with Rithmah in verse 18. The evidence presented for the identification cannot be described as compelling, so we will take the simple position that we cannot know for sure which of the stations mentioned is one and the same as Kadesh Barnea. Working with average distances between stations suggests that Terah (Num. 33:27) is the most likely candidate, but we cannot know. Frankly, it doesn't really matter. Alternatively, Kadesh Barnea could be a more specific name, possibly of a watering hole or the like, that was located in a district of a different name, in the same way that San Rafael is a city in Marin County, and Numbers 33 uses the district name. In short, the lack of appearance of the name “Kadesh Barnea” in verses 16-35 of Numbers 33 is no major impediment to the view presented here. Third, we have the subjective argument against identifying the Kadesh of Numbers 20 with the Kadesh Barnea of chapters thirteen and fourteen. When the Israelites reached Kadesh, they threw up their arms in despair: And why have you made us come up out of Egypt, to bring us to this evil place ? It is not a place of grain or figs or vines or pomegranates; nor is there any water to drink (Num. 20:5). As the Creator of all mankind, God has the right to punish His people when they rebel against Him. And no doubt, as a God of perfect justice, He did exactly that by imposing forty years of wilderness living upon them. However, God is not only perfectly just, He is perfectly good. Would the God of all goodness force His people to live for nineteen or more years in an “evil place”? God is just, but He's not vindictive. Finally, we have the testimony of Numbers 20:16 that this Kadesh was “a city on the edge of [Edom's] border”. As mentioned earlier, it is very hard to imagine that the Israelites could have set their tents up against a city wall for any protracted period without coming under attack from the residents, especially if water were in such short supply! And particularly if that city was slap up against Edom's border. The Edomites attacked Israel shortly after these words were sent to the King of Edom in a message (vs. 20). To propose that the Israelites spent many years unmolested within slingshot of this Kadesh doesn't make any sense. Some scholars have recognized that we must be dealing with two different Kadeshes. Most of them, however, attribute the confusion to the belief that the Pentateuch was compiled late in history from a number of different original sources, a theory known as the “documentary hypothesis”. Thus, Bacon makes a distinction between the Kadesh Barnea of J (the “Jahwist source”) and the Kadesh of E (the “Elohist source”). He remarks that, “E did not bring them [Israelites] to Kadesh until the end of the period of wandering. Israel's objective point is now the plains of Moab, and direct access is sought through the territory of Edom. Kadesh is the station reached on Edom's western border” (1895, p. 235). He is right on the location of this Kadesh though wrong in his view of biblical historiography. Naturally, any reconstruction that treats two different places as if they were one and the same cannot help but come to grief. Admittedly some of the evidence just presented can be interpreted differently, but once all the bits and pieces have been worked into a harmonious whole the reader will see that the scenario presented here concerning two Kadeshes must be correct. Kadesh ain't Kadesh. Problems with the traditional site of Kadesh BarneaLet's now consider some problems that attend the traditional siting of Kadesh Barnea at Ain el-Qudeirat in the north of the Sinai Peninsula. (See Figure 1,showing the traditional locations of Mount Sinai and Kadesh Barnea and the route supposedly taken between the two.) The purpose of showing how baseless this identification proves to be is to demonstrate the need to take another tack entirely. In “Somewhere, over the Red Sea” we showed that Mount Sinai is located in the Hejaz region of north-west Saudi Arabia.This paper will show how admirably the biblical data concerning the route taken from Mount Sinai to the Holy Land fits that thesis. First of all, why do traditionalists place Kadesh Barnea at Ain el-Qudeirat? The story of the selection of this location would make a highly readable book in its own right, with characters as colorful and famous as Lawrence of Arabia playing a leading role. The choice is based on flimsy reasoning. Hershel Shanks , well-known editor of Biblical Archaeology Review, summarizes: Most scholars accept the identification of the site as modern Ein el-Kudeirat. Its location, the impressive tell, the availability of water and other environmental conditions make it by far the best candidate — in some ways the only candidate — for Kadesh-Barnea (2011, p. 55). Other than the fact that Ain el-Qudeirat is the sole remaining candidate after all the impossible alternatives for fitting with traditional notions about the Red Sea crossing and the location of Mount Sinai are eliminated, the identification fails miserably to carry weight. One wonders why Hershel Shanks makes mention of a tell4, since the Israelites did not build a city during their stopover at Kadesh Barnea. The main reason for the choice comes down to the slim criterion of livability. Another author adds “the site's location on two important ancient routes”5 as a reason for making the choice. For some peculiar reason, Hershel Shanks doesn't make mention of the one item of objective evidence that might be massaged to stand in its favor: located at a distance of 150 miles from Jebel Musa, Ain el-Qudeirat may comply with the important criterion of being located eleven days journey from Mount Sinai (Deut. 1:2). Add twenty miles for the indirectness of the path followed, and you have 170 miles, averaging out at 15.5 miles per day's journey. Maybe, just maybe, 15.5 miles can be accepted as a day's journey. More on this point later. In a few particulars , the biblical data provided in Scripture about the route taken by the Israelites after leaving Mount Sinai can be made to fit both the traditional reconstruction and the reconstruction presented here. For instance, consider a verse sited earlier: So we departed from Horeb, and went through all that great and terrible wilderness which you saw on the way to the mountains of the Amorites, as the Lord our God had commanded us. Then we came to Kadesh Barnea (Deut. 1:19). This description fits the terrain between Jebel Musa and Ain el-Qudeirat well. It also admirably describes the arid plateau fringing the enormous Arabian Desert that our reconstruction proposes as the setting for Israel's post-Sinai migration. Precipitation levels and temperatures in both the Sinai Peninsula and this area of the vast Jordanian plateau are about the same, favoring neither one over the other as the more “terrible”. Another example can be found in Deuteronomy 1:20-21, quoted earlier, but repeated here for convenience: You have come to the mountains of the Amorites, which the Lord our God is giving us. Look, the Lord your God has set the land before you; go up and possess it… Both Ain el-Qudeirat and the location proposed in this paper for Kadesh Barnea make perfect sense of this passage since both lie near the Promised Land. As a comparison, Ain el-Qudeirat lies 46 miles from Beersheba as the crow flies while our proposed location is about 75 miles away. Hebron is 68 miles from our site while it is 73 miles from Ain el-Qudeirat. Neither site trumps the other in terms of proximity to “the mountains of the Amorites” (synonymous with the Canaanites and Amalekites). Certain facts, however, eliminate Ain el-Qudeirat from consideration. Consider the archaeological evidence. If the Israelites had lived there for nineteen or more years, archaeologists would be able to find some trace of their encampment in the form of the usual lineup of artifactual suspects — potsherds, necklace beads, leather straps, metal pieces from carts, faience, remnants of stone hearths, as well as more mundane scraps such as animal and fish bones — not to mention evidence of burials. So what has been found? As Dever (1990) points out, Israeli excavations at the site have revealed “not so much as a potsherd earlier than the tenth century B.C.”. Not looking good, is it? (Remember, the Exodus occurred in the fifteenth century.) Now consider some of the biblical clues. First, we have the story of the failed attack by Israel from Kadesh Barnea, mentioned briefly earlier, against nearby Amorites immediately after God had sentenced them to forty years wandering: Then Moses told these words [concerning the forty years postponement] to all the children of Israel, and the people mourned greatly. And they rose early in the morning and went up to the top of the mountain, saying, “Here we are, and we will go up to the place which the Lord has promised, for we have sinned!” And Moses said, “Now why do you transgress the command of the Lord? For this will not succeed. Do not go up, lest you be defeated by your enemies, for the Lord is not among you. For the Amalekites and the Canaanites are there before you, and you shall fall by the sword; because you have turned away from the Lord, the Lord will not be with you.” But they presumed to go up to the mountaintop… Then the Amalekites and the Canaanites who dwelt in that mountain came down and attacked them, and drove them back as far as Hormah (Num. 14:39-45). The terms “mountain” and “mountaintop” in this context would better be translated “highlands”; you would be hard-pressed to find a single mountain with sufficient area to be home to two different peoples. The salient point here is that from Kadesh Barnea the Israelites had to ascend into highlands to meet the foe. The passage reads as if it was close enough for them to do it within a day. One area lying fifteen to twenty miles east and slightly south of Ain el-Qudeirat matches the description quite well. With Ain el-Qudeirat lying at 400 meters elevation and with the highest peak in this area at Mount Ramon6 at 1000 meters, they would certainly have had to climb. So far, all seems well. That is, until we factor in another reference to the same incident that changes the complexion considerably: And the Amorites who dwelt in that mountain came out against you and chased you as bees do, and drove you back from Seir [Edom] to Hormah (Deut. 1:44). See the problem? The area the Israelites assaulted bordered on Mount Seir (Edom, see Figure 2) and the Israelites must have pressed their charge right up against it for the passage to make any sense. Mount Ramon is about forty miles from the nearest border with Edom, with extensive lowlands, including the Arabah,7 being interposed between the two, a fact that simply doesn't jibe with the above passage (see Figure 2). As the old saying goes, “The devil is in the detail”. Any reconstruction must fit all the data to be convincing. As we will see, this passage from the Pentateuch fits beautifully with our reconstruction. Figure 3 shows a closeup of the proximity of our Kadesh Barnea to the “mountains of the Amorites”. (The area in yellow does not represent the entirety of the Promised Land but just that part of it relevant to the current discussion.) We will explain later exactly where this region is located. For the time being, note how close the highest peak, probably the “mountaintop” of Numbers 14:44, is to Edom, explaining how it was that the Amorites drove the Israelites “back from Seir”. We conclude that the traditional siting of Kadesh Barnea at Ain el-Qudeirat in the northern Sinai fails to meet the biblical criteria. As we saw in “Somewhere Over the Red Sea”, t he identification of Jebel Musa with Mount Sinai must be rejected. Putting these two facts together suggests that the entire orthodox edifice needs a bulldozer run through its middle and a new edifice constructed in its place. These two papers provide a compelling reconstruction. Reconstructing the trailTo have any chance of plotting the route taken by the Israelites with any degree of accuracy you must have at least a few dots, representing points on the route, you can be confident of. Enlightened sleuthing can then be employed to add more dots with some degree of accuracy. Finally, you join the dots. Of critical importance is the starting point; get it wrong and you will be off on a wild goose chase. We already have Mount Sinai marked on the map.8 Where do we go from there? We will start with the key facts presented in Deuteronomy 1:2: It is eleven days' journey from Horeb by way of Mount Seir to Kadesh Barnea. This verse provides two critical clues that need to be carefully considered: • The distance These clues won't enable us to triumphantly thrust a pin into the map but will give us a very helpful guideline which can be further refined by other hints. The distanceExactly what is a day's journey? Contrary to some opinions, a day's journey was a fixed distance; it did not vary with the terrain. True, how far anybody can go in a day varies dramatically with the person and with the terrain encountered. The expression can be meaningful in communication, however, only if it refers to a conventional fixed distance known by all. How far any given person travelled in a day is irrelevant. The Israelites took months to travel the eleven days' journey from Sinai to Kadesh Barnea! The question remains, how far was a day's journey? Nobody knows for sure, but we can be fairly confident of establishing a range of possibilities. We will take the position found in The Illustrated Bible Dictionary , which says, “Presumably a day's journey was between eighteen and twenty-five miles” (ed. Douglas 1980, p. 369). Using this range as our guide leads us to search for Kadesh Barnea somewhere between 200 (198 to be precise) and 275 miles walking distance from Mount Sinai along the most logical route. The directionThe Deuteronomy passage reveals that the Israelites traveled “by way of Mount Seir”. The Hebrew construction, derekh ha-Seir, can be read a few different ways. • they went “via Mount Seir”, or, The New King James Version (NKJV) takes the first meaning, suggesting that the Israelites went via Mt Seir to get to Kadesh Barnea. This English construction implies they went beyond Mount Seir before coming to a halt. The New International Version (NIV) takes the third meaning, translating it, “It takes eleven days to go from Horeb to Kadesh Barnea by the Mount Seir road”. Zecharia Kallai takes this construction to show that, “In this case, therefore, Kadesh-barnea is on the road that leads from Horeb to Mount Seir…” (1995). He reads the passage as suggesting the Israelites came to a halt before they reached Mount Seir. Although the three English renditions each imply something a little different from each other, the Hebrew is neutral, and on its own gives no help in deciding whether they stopped short of the destination (Mount Seir) or went beyond it. We propose, however, that the evidence suggests that in this passage the term is referring directly to a road that served as a major trading route linking the fabled land of Sheba and other regions in the south-west of Saudi Arabia with Egypt, the Levant, and Syria (the NIV interpretation). Describing this inland trade route for carrying precious goods, Haran remarks that this ancient caravan route, “ began in Shabwa in southwestern Arabia, passed through the Sheba region and swept directly north parallel to the Red Sea coast… from the El-Ola oasis a northward branch carried the incense to Petra and Damascus” (1995, caption to Figure 4). See Figure 4 for an overview of the route. Commonsense suggests that the Israelites followed this trading road leading to Mount Seir for at least part of their march towards Kadesh Barnea. Whether they stopped shy of Mount Seir or shot beyond it cannot be determined from the direction component of the Deuteronomy passage. Figure 5 outlines the most likely route taken by the Israelites from Har Kodesh towards Kadesh Barnea. Putting the two togetherWe are going to find Kadesh Barnea somewhere in the direction of Mount Seir, between roughly 200 and 275 miles from Har Kodesh9 taking the most sensible route, first, from Har Kodesh to the trade route and then, second, following the trade route, Mount Seir Road, towards Edom. That the Israelites broke away from the road before it entered Edom is evidenced by the fact that Scripture doesn't mention any interaction between the two peoples. They would have continued north roughly parallel to, and some miles east of, Edom's eastern border to the point where an eleven days' journey ended. No guesswork is required to figure out the route taken from Har Kodesh to the Mount Seir Road. The reader is encouraged to dust off Google Earth and paste these coordinates into it: 27 50 38 35 35 25. Zoom in or out as needed to an eye altitude of about 8 miles (12 kilometers). You are looking at the western edge of the Mount Sinai camping area. Now make sure Roads is enabled and you will see a faint yellow line running through the camping area. This line marks out the path of a road running generally east-west and which connects two major north-south highways. Remembering that modern roads are built where the terrain presents the least hindrance to human movement, you can conclude that this road marks out the route the Israelites would have taken. Follow this road towards the east until it meets Highway 80.10 From here to the top of the plateau is another four miles. For those who don't have access to Google Earth, Figure 6 shows the route they would have taken. This track climbs roughly 800 meters over a walking distance of about thirty miles, a gentle gradient. A close-up view shows that it follows a wide, sandy wadi most of the way, a route that would present little problem for carts and cattle. As an aside, this track would have taken them right past the rock of Horeb on the way. We can be fairly confident that none of the stopovers listed in Numbers 33 are to be located along this narrow, circuitous trail to the top of the plateau. The people would have been strung out over many miles during that leg of their pilgrimage, so setting up the tabernacle of the congregation would have proven pointless. That the first station after leaving Mount Sinai — Kibroth Hattaavah — is to be found on the top of the plateau is supported by the quail incident. Please read all about it for yourself in Numbers 11. At this first stopover after leaving the balmy delights of Mount Sinai, the people began to feel terribly sorry for themselves. When they whined about the lack of meat, God whipped up a quail tempest, as described in verse 31: Now a wind went out from the Lord, and it brought quail from the sea and left them fluttering near the camp, about a day's journey on this side and about a day's journey on the other side, all around the camp, and about two cubits above the surface of the ground. The topography implied here is obviously fairly flat, as the people could not have gone clambering up canyon walls and down the other side for up to ten miles in any direction to gather fluttering birds. Being piled up to a certain height on the ground again implies flat ground. These conditions were realized on the plateau. Kibroth Hattaavah, then, can be placed on the map with some accuracy. It's the only stopover that can be reasonably confidently pinpointed between Har Kodesh and Kadesh Barnea. Supporting this location is the statement in Numbers 10:33 that this stopover was a three-day journey from Mount Sinai, suggesting it lay between 55 and 75 miles from Mount Sinai, which puts you on top of the plateau in precisely the area we are suggesting. Upon leaving Kibroth Hattaavah they would most likely have made a beeline across the flat landscape to the ancient town of Qurayyah,11 located about 38 miles north west of modern Tabuk. The Mount Seir Road almost certainly passed very close to Tabuk and through Qurayyah. Therefore, the Israelites would have intersected the trading route near Qurayyah. Whether or not a town stood near modern Tabuk in Moses' time is unclear, but archaeological studies at Qurayyah show that the town “was occupied from the Late Bronze Age or earlier” (Dayton 1972, p. 21). That puts it right in the time frame we are talking about. Who would doubt that this town served travelers along the ancient trade route? How does all this help us locate Kadesh Barnea? The on-the-ground distance from Har Kodesh to Qurayya, following the path of the modern road, is about 110 miles. Now all we need do is to proceed from Qurayyah towards Mount Seir, taking the minimum value for a day's journey (18 miles) to mark the southernmost point of the range of likely locations for Kadesh Barnea and the maximum value (25 miles) for the northernmost. Following the probable route of the Mount Seir Road, the short value brings you to the vicinity of the modern city of Maan, Jordan,12 which was very close to the Edomite border, and from where the trading route plunged into Edom and proceeded onto the famed rose-red citadel of Petra.13 (Petra's famous buildings were not erected by the Edomites but by the Nabateans some hundreds of years later.) If a day's journey was greater than the 18 mile value, they probably would have taken a route that bypassed Maan ten to fifteen miles to its east and headed north across the vast, flat desert. Following that route, and taking the longest value for a day's journey, would have brought them to Al Qatrana, Jordan.14 In sum, we can establish a 75-mile, north-south zone of potentiality for the location of Kadesh Barnea. We can be confident that the zone is narrow in its east-west dimensions due to the statement in Deuteronomy 1:20 that at Kadesh Barnea they had “come to the mountains of the Amorites” and were close enough to enter and conquer. Kadesh Barnea could not be very far to the east. See Figure 7 for clarification of the range of potential sites. Compare this zone of potential Kadesh Barnea sites with the results you would come up with if you applied exactly the same method taking Jebel Musa, the traditional location for Mount Sinai, as the starting point. Taking the shorter value for a day's journey would take you way past Ain el-Qudeirat all the way to Beersheba, Israel 15, even adjusting for the indirect path they would have taken to get out of the southern mountains and to satisfy the requirement to go in the direction of Mount Seir (Deut. 1:2). See the problem? Kadesh Barnea was located near the Promised Land, but not in it (Deut. 1:20). Taking the longer value for a day's journey would place Kadesh Barnea 35 miles north of Jerusalem! It's time we abandoned the fairytale that Jebel Musa and Ain el-Qudeirat comply with the biblical data. Where is it, then?Where, then, is Kadesh Barnea ? Can we narrow down its likely location any further than we have already done with our “zone of potentiality”? Yes, we can. Once again, over-confidence would be foolish, but we can come close to pinpointing its location by eliminating the alternatives, leading, like following the lines of a spiral towards its centre, to a point of greatest probability. To do so requires introducing a totally new idea into the equation which, at first sight, might seem too bold to uphold but which, upon rumination, makes perfect sense. The new idea is simply this: in Moses' day, a tiny territory occupied by Canaanites and Amalekites was sandwiched between the petty states of Edom (Mount Seir) in the south and Moab in the north. For the sake of convenience, we will dub this territory Canamalia — a better choice, wouldn't you agree, than the logical alternative, Amoria. We propose that Kadesh Barnea lay a little east of Canamalia's eastern boundary. Where would the eastern boundary be located? It is impossible to know precisely how far east the borders of these small states extended at that time, but we cannot be far off the mark to say that they would almost certainly not have gone any further east than the modern Desert Highway in Jordan (Hwy 15), which lies roughly thirty to thirty-five miles east of the great rift valley in which the Dead Sea and the Arabah lie. No known site of any major town from that period is found east of that highway, and most lie between ten and twenty miles to its west.16 The Edomite cities of Petra and Bozrah, for instance, lie roughly sixteen miles west of the highway. One of the most eastern archaeological sites in ancient Moab is found at Khirbat al-Balu17, and it, too, lies about 16 miles west of the Desert Highway. Archaeological surveys have found a number of shards from around Moses' time (MacDonald 2000, p. 99) — the Late Bronze Age — on the Kerak Plateau in Moabite territory. It, too, is located about fifteen miles west of the Desert Highway. We can safely set the eastern border of all three of these principalities no further east than the Desert Highway. Figure 8 shows the approximate extent of the well-known states of Edom and Moab as well as of the proposed state of Canamalia. (Figure 3shows Canamalia in greater detail; there it is designated “the mountains of the Amorites”.) On what basis can we posit the existence of the Amalekite/Canaanite kingdom of Canamalia? How does this proposal aid our cause? The argument is straightforward enough. Consider these points. 1. Deuteronomy 1:20-21Remember this important passage? When the Israelites arrived at Kadesh Barnea, Moses told them, You have come to the mountains of the Amorites, which the Lord our God is giving us. Look, the Lord your God has set the land before you; go up and possess it, as the Lord God of your fathers has spoken to you; do not fear or be discouraged. Neither Edom nor Moab was on Israel's radar screen as part of their divinely-ordained possession; Israel was not to inherit “a foot's worth” of either territory (Deut. 2:5, 9). If these states were joined at the hip, thus creating a continuous wedge separating Kadesh Barnea from the Holy Land to the west, Moses could not have said, “You have come to the mountains of the Amorites”. Canamalia solves the problem simply and elegantly. This “mountain of the Amorites” consisted of an easterly, highland extension of lowland Amalekite/Canaanite territory (Num. 14:25), probably the northernmost part of the valley of the Arabah at the southernmost end of the Dead Sea. As to the extent of this proposed territory, one can intelligently surmise. Geography provides logical constraints for establishing Canamalia's northern and southern borders. Later in history the Edomites moved into this Amalekite/Canaanite enclave, creating friction with Israel since it was land intended for them. In Moses' day, we propose, the border between Edom and Canamalia lay along Wadi Dana. One writer describes this wadi as “ one of the most dramatic and unspoilt wadis in the Southern Rift Margins… The surrounding hills reach 1500 m, and hold a rich and distinctive, high altitude avifauna. The wadi itself, flanked by red sandstone cliffs and narrow side gorges, runs down to Wadi Araba, and contains a range of habitats, many of which can only be reached on foot”.18 The later, Iron Age Edomite stronghold of Bozrah19 was perched on the southern lip of this wadi near its easternmost point. The border between Canamalia and Moab undoubtedly coincided with Moab's “classical” southern boundary — Wadi al-Hasa. This wadi supposedly provides more spectacular scenery than Wadi Dana, with its “magnificent hanging gardens, narrow gorges and hot springs” making for spectacular walking tours.20 These two gorges, then, make for logical limits to Canamalia country. (See Figure 9 relief map showing these natural boundaries reasonably clearly.) If correct, Canamalia attained a maximum north-south dimension of about seventeen miles. Its westernmost boundary would have fallen roughly in line with the Arabah, although the statement in Numbers 14:25 that the Canaanites and Amalekites dwelt in “the valley” may mean that they occupied parts of the Arabah as well as the adjacent escarpment and highlands. The below-sea-level, modern city of Safi21 on the south-eastern shore of the Dead Sea and through which the Wadi al-Hasa flows just before entering the Dead Sea, may well have been a Canamalian settlement at that time. That a settlement existed there is suggested by the discovery there of a few Late Bronze Age sherds.22 One can but guess at Canamalia's eastern boundary, but we cannot be too far out if we put it no further east than the modern Jordanian town of Al Hasa.23 Canamalia's breadth would then be roughly thirty to thirty five miles. The topography of this proposed southeastern tail of the Promised Land matches the description given in Numbers 14:40-45 concerning the Israelite attempt to storm it from Kadesh Barnea: And they rose early in the morning and went up to the top of the mountain, saying, “Here we are, and we will go up to the place which the Lord has promised, for we have sinned!” And Moses said, “Now why do you transgress the command of the Lord? For this will not succeed. Do not go up, lest you be defeated by your enemies, for the Lord is not among you. For the Amalekites and the Canaanites are there before you, and you shall fall by the sword; because you have turned away from the Lord, the Lord will not be with you”. But they presumed to go up to the mountaintop… Then the Amalekites and the Canaanites who dwelt in that mountain came down and attacked them, and drove them back as far as Hormah (Num. 14:40-45). This account shows that from their camp at Kadesh Barnea they had to “go up” into “the top of the mountain/highlands”. The proposed location of Kadesh Barnea, soon to be revealed, is at an altitude of about 850 meters, while Canamalia is around 1200 meters elevation, requiring that they “go up” to reach it. Equally important in supporting this location is Deuteronomy 1:44, a verse which we saw earlier creates a major problem for the Ain el-Qudeirat identification with Kadesh Barnea. The verse states that the enemy, “drove you back from Seir [Edom] to Hormah”. In spite of the uncertainty surrounding Hormah's whereabouts, this battlefield description suggests that the Israelites attempted to storm the highest peak in Canamalia (1480 meters)24 located a stone's throw from Canamalia's proposed border with Edom, but were beaten back from Edom. Fits perfectly. 2. The route to the plains of MoabAll scenarios agree in their fundamentals when it comes to the last leg of the journey — a flanking movement around the eastern side of Moab starting from the Arabah somewhere south of the Dead Sea and ending alongside the Jordan River six or seven miles north of the Dead Sea. The question is, how did they get to the eastern side of Moab from the Arabah without passing through either Edomite or Moabite territory? Although some scholars believe that Numbers 33:44 suggests that the Israelites camped inside Moabite territory at Ije Abarim (MacDonald, p. 72), a straightforward passage proves them wrong in their understanding.25 That they did not enter either Edomite or Moabite territory at any time during their march is made clear in Judges 11:14-18: So Jephthah again sent messengers to the king of the people of Ammon, and said to him, “Thus says Jephthah: ‘Israel did not take away the land of Moab, nor the land of the people of Ammon; for when Israel came up from Egypt, they walked through the wilderness as far as the Red Sea and came to Kadesh. Then Israel sent messengers to the king of Edom, saying, “Please let me pass through your land.” But the king of Edom would not heed. And in like manner they sent to the king of Moab, but he would not consent. So Israel remained in Kadesh. And they went along through the wilderness and bypassed the land of Edom and the land of Moab, came to the east side of the land of Moab, and encamped on the other side of the Arnon. But they did not enter the border of Moab, for the Arnon was the border of Moab'” (Jdg. 11:14-18). Jephthah, a judge of Israel, spoke these words a couple of hundred years after Moses' time. Note carefully that the Israelites bypassed both Edom and Moab when their respective kings refused to give permission to pass through their territory. The Hebrew word, sabab, expresses the idea expressed by English terms such as “go around, surround, encircle” (Brown, Driver, & Briggs 1972, p. 685). As we will see later, they bypassed Edom on its western side and Moab on its eastern side. Jephthah also explicitly asserts that they “did not enter the border of Moab”. With these facts up our sleeve, we are virtually forced to draw the same conclusion as before; an Amorite enclave separated Moab in the north from Edom in the south. For some unexplained reason, the Israelites were able to ascend unimpeded through this rugged territory to bring them to the east of Moab even though, nearly forty years earlier, they had exchanged blows with Canamalia's inhabitants. Time can do strange things when it comes to international relations. In addition, as experience shows, interpersonal relationships can thrive between peoples whose relationships are strained at the official level. After Israel's abortive attempt to dislodge its inhabitants because God refused to assist Israel (Num. 14:42), it would seem both sides settled down to an uneasy truce as neighbors for many years. Possibly over time erstwhile foes became friends. Exactly what Moses — or, more importantly, God — would have thought of such a rapprochement one can but guess at. We should note the irony of this situation. God had told Moses not to provoke the Edomites and Moabites but to annihilate the Amorites. Yet is was the Amorites who allowed Israel to pass through their territory when the Edomites and Moabites refused permission. Hot on the trailFinally, we are ready to narrow down the location of Kadesh Barnea: it must lie east of Canamalia. If our theory as to the location of Canamalia's northern and southern borders along natural topographic features is correct, then the eastern border of Canamalia was a mere 11 miles or so in length, lying roughly between the modern towns of Al Hasa in the north and Jurf Al Darawish26 to the south. Now we're getting somewhere. But we're not done. We can narrow our search down much further. What one requirement above all others is essential to life? You're right. Water. The presence of water at Ain el-Qudeirat is a major factor in its selection as the front-runner in the eyes of traditionalists. Naturally, a ready supply of water will attract other people, too; how the Israelites were able to monopolize the supply remains an open question. Was it the fear factor mentioned earlier? Kadesh Barnea was in or near Amalekite territory, and we remember what happened at Rephidim. Then there's the other “thing” that talks as loud as fear — money. The Israelites came loaded to the gills with treasure from Egypt, their cart axles bending under the weight; perhaps they leased the site in perpetuity. So fire up your Google Earth and looky here: 30 48 37 36 00 34. You have an area of about three square miles covered with trees. Trees mean water. Figure 10 provides a view of the trees from about 5 miles in altitude. The skeptic might assert that this water is pumped from underground for use at a nearby phosphate mine. How can one prove that this water flowed naturally thousands of years ago? Well, it's times like this one would love to get one's feet on the ground. Examination of the landscape to the west of the clump of trees strongly suggests that water has flowed here over a long period. The nearby town of Al Hasa is split into two sections by a stream bed originating in the copse. Tracing the bed west shows that flowing water coming from the woods has, over time — and it would require much more time than any mine has been tapping the water supply — cut into the bedrock. True, the aerial shots show no water flowing along the wadi at this time, but we have reason to believe conditions were moister back then than today. The presence of the stream bed in the town of Al Hasa proves that water flows at least periodically, and the presence of trees in the gorge cut into the rock downstream of Al Hasa shows that it flows regularly. Even an ephemeral flow would have sufficed to provide a permanent supply if cisterns were dug or impoundments built. The evidence piles up to suggest we can place Kadesh Barnea somewhere in the vicinity of the extensive woods near the modern town of Al Hasa. The modern Desert Highway right nearby probably traces the route of an ancient trading road. Before the Israelites arrived, Kadesh Barnea may well have been a resting place for merchants. It fits. Who can see any fatal flaws? From here on, the names Kadesh Barnea and Al Hasa will be used interchangeably.

1 38 32 17 33 58 26 [Back] 2 30 38 54 34 25 20 [Back] 3 A synonym for Canaanites [Back] 4 A large mound of rubble and earth consisting of the accumulated remains of ancient settlements [Back] 5 Lawrence of Arabia as Archeologist [Back] 6 30 29 58 34 38 17 [Back] 7 A section of the Jordan Rift Valley running in a north-south orientation between the southern end of the Dead Sea and the northern tip of the Gulf of Aqaba. (The area lying between Ezion Geber and Zalmonah on Figure 11.) From the Dead Sea, where the elevation is 350 metres below sea level, the altitude rises as you head towards the Gulf of Aqaba, reaching sea level about 30 miles south of the Dead Sea, then continues to rise gradually to about 240 metres above sea level before sloping back to sea level at the northern end of the Gulf. Its width ranges from six to thirteen miles. The Arabah is an exceedingly hot and dry environment, resulting in very limited human settlement. [Back] 8 27 51 33 35 44 29 [Back] 9 The author's name for the mountain he believes to be Mount Sinai; it means “holy mountain” [Back] 10 27 48 13 35 59 49 [Back] 11 28 51 12 36 16 37 [Back] 12 30 10 41 35 44 49 [Back] 13 30 19 20 35 28 42 [Back] 14 31 15 04 36 01 37 [Back] 15 31 14 53 34 48 35 [Back] 16 Most of the sites east of the Jordan/Dead Sea are located along one or other of a series of north-south-flowing wadis “in the highlands at the Eastern Rim of the Wadi ‘Arabah–Jordan Graben”. It was along these wadis that, “much of the country's agricultural activities took place” (MacDonald 2000, p.27) and, therefore, occupation centres were located. [Back] 17 31 21 59 35 46 58 [Back] 19 30 44 49 35 36 10 [Back] 20 Jordan Beauty Travel and Tours [Back] 21 31 01 22 35 27 27 [Back] 22 Chronology of the Wadi Arabah [Back] 23 30 49 16 35 59 14 [Back] 24 30 46 18 35 38 33 [Back] 25 The Hebrew seems capable of a range of meaning from “inside the territory of” to “alongside the border of”. [Back] 26 30 41 10 35 52 04 [Back] |

|

|

|

Dawn to Dusk publications |

Other printed material |

On the Web |

|

Dawn to Dusk publications |

Dawn to Dusk publications |

Dawn to Dusk publications |

| Edited and expanded copies of this article, in reprint pamphlet form, can be purchased by going to the reprints order page. As well as reprints, Dawn to Dusk offers books in printed form and on CD-ROM. We mail to anywhere in the world! For more information on what is available, prices, and how to order, click the icon. |