|

Squirmy wormies, wondrous wormies

Last Sunday, our field naturalists group made its annual excursion to the Penguin, Tasmania, rock platform at low tide. Near-perfect conditions and a bumper turnout combined to make it a truly memorable day. So too did our finds. Not only did we uncover the biggest blue-ringed octopus I have ever seen, and a charismatic little cuttlefish I had never seen, I, personally, was most gratified by finding an inconspicuous-looking, dirty, soft lump under a boulder. Though the whole lump was only about the size of a nickel, I was confident I had found something I often look for but hardly ever find - a nemertean, or ribbon worm. Sure enough, upon gently placing it in a small pool of water the tangle began to heave and then, before our bulging eyes, the tip of a piece of thread began to crawl out from within the knot. The loose end kept on crawling away from the lump and within a minute the tangled knot had unraveled into a six-inch long, very thin, flattened, pale-colored, candy-striped worm. Soon it had magically stretched to about ten inches. It could, if it so chose, extend itself to at least a couple of feet long. (Some years ago I kept a vivid yellow specimen in a fish tank at home and discovered it, one evening when I turned on the light, stretched out along the entire length of the tank.)

Nemerteans may "only" be "worms" but I'm here to tell you that their design attests to the genius of their bio-engineer Creator. Not to mention His sense of beauty. Many of them are vividly colored and gorgeously-patterned; not even King Solomon in all his glory.

About one thousand species have been described from around the world. The vast majority are found under rocks, in sand, or among seaweed in salt water, but a few float in the open ocean, while others live in freshwater and others still among damp leaf litter. Most species are carnivorous, the majority feeding on live prey while a few practice scavenging. A small number are suctorial feeders and one unusual genus consists of suspension feeders. One genus, Carcinonemertes, has long been known as a specialized egg predator of crabs, with up to 32 worms in various stages of the species' life cycle living on one host crab. More recent research has discovered that "the life history of this group has revealed that their diversity has been greatly underestimated".1 Why am I not surprised?

Don't let the apparent simplicity of their body plan - long, thin, smooth, and slimy - fool you. Ribbon worms exhibit a number of remarkable features, not least of which is their staggering power of extension and contraction; watching one just get longer and longer would have to switch on the most turned-off soul.

Nemerteans give evolutionists nightmares. Some invertebrate animals start off their lives as larvae which then undergo a process of metamorphosis to reach the adult condition. Other invertebrates undergo direct development, hatching out of the egg as a miniature version of the adult form and then growing larger. Ribbon worms (and peanut worms) exhibit both forms of development among different members of the group - some reach maturity directly while others take the circuitous, metamorphic path. Isn't it amazing what millions of years of evolution can do?! Yeh,

|

sure. The larval stage of those that metamorphose (known as a pilidium) develops an ingrowth of four or five pockets which eventually fuse around the gut forming a continuous cavity around an inner kernel, separating the inner kernel from a surrounding husk. The inner mass undergoes a rather complicated metamorphosis into a tiny dense worm which lives like a parasite inside its larval covering. At length the worm is released and drops like a bomb to the sea floor, while the ciliated husk swims off and dies. What sort of mind does it take to dream up a scenario like that?

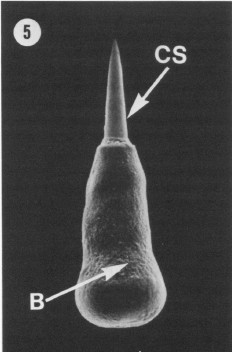

Perhaps the crowning glory of ribbon worms is the proboscis. All species contain a special sac inside which lies the proboscis apparatus, a "unique and a visibly-outstanding feature of the Nemertea".2 The proboscis comes in two main forms (see below). The vast majority consist of a base with a hard stylet mounted at its front end. When stimulated by the presence of prey, the sac contracts at lightning speed, causing the proboscis to turn itself inside out and to be shot out through a special pore above the mouth. Accuracy can be critical for those species that eat shelled prey such as tiny crustaceans. The tip of the proboscis must strike against vulnerable softer body plates, at which it penetrates the "shell" and injects a swift-acting toxin. The other main kind, found in seven species worldwide as of 2006, does not have a penetrating stylet. Rather, the proboscis is branched and, when everted, "wriggles, contracts, and expands over a surprising area,"3 entangling the prey.

In a brilliant piece of providential care and masterful engineering, ribbon worms continue to produce reserve stylets throughout life, providing replacements for stylets damaged in action. Although it's a little technical, I urge readers to study the following outline explanation of the process of stylet replacement:

One to several reserve stylets are ejected from the reserve stylet sac, apparently by contractions of the surrounding muscles and/or the squamous epithelial cell processes of the sac wall. The stylets travel through the duct of the styiet sac and enter the lumen of the proboscis near the region where the anterior end of the basis is located. Once in the lumen, the stylets are actively moved about by contractions of the proboscis and the musculature of the body wall. One stylet is thereby oriented with its proximal piece toward the basis, and contractions of the longitudinal muscle in the wall of the proboscis draw the stylet toward the basis. The stylet in proximity to the basis becomes attached, presumably owing to adhesive properties of the basis granules or some other substances in the basis. The basis may attach more readily to the thin peripheral layer of organic material in the proximal piece, and thus facilitate orientation of the stylet during stylet replacement.4

An accident of evolution? Ridiculous. Carefully and wondrously worked out in minute detail by the Creator, wouldn't you say?

I reckon nemerteans are brilliant critters, and I can hardly wait to observe them up close and "au naturel" when I am changed to immortal à la 1 Corinthians 15:44.

|

|

1 Wickham and Kuris, Diversity among nemertean egg predators of decapod crustaceans, Hydrobiologia, 156: 23 -30 (1988)

2 McDermott and Roe, Food, Feeding Behavior and Feeding Ecology of Nemerteans, American Zoologist, 25:113-125 (1985)

3 W. J. Dakin, Australian Seashores, p. 199

4 S. A. Stricker, The Stylet Apparatus of Monostiliferous Hoplonemerteans, American Zoologist, 25:87-97 (1985)

Dissected-out examples of the two main kinds of proboscis in ribbon worms (American Zoologist and Journal of Natural History)

|